Patient in a neuropsychiatric care home

Patient in a neuropsychiatric care home

In October 2025, Viktoriia Budkina, a legally incapacitated Moscow resident, had her arms amputated as a result of the brutal abuse she sustained from the orderlies of the psychiatric care home where she lives. The facility is one of the psycho-neurological residential facilities that Moscow City Hall has rebranded as “social homes” for propaganda purposes. People whose rights are restricted for medical or social reasons can end up living in these institutions for decades, helpless against violence and humiliation. For years, volunteers and activists have tried to make the system more humane. Under wartime conditions, however, defending patients’ rights has become far more difficult.

What is happening to residents of Moscow’s psychiatric care homes

Activism in a concentration camp

Russia’s PNI system after 2022

People deserve dignity

On Oct. 14, during rounds at the Obruchevsky social home in southwest Moscow, a nurse and a duty caregiver discovered that other staff members had tied the hands of 20-year-old Viktoriia Budkina with wool leggings, cinching them too tightly. Viktoriia, a Group I disabled person with a severe mental illness, was unable to call for help and remained in that position so long she developed gangrene. By the time Viktoriia was taken to the hospital, her hands could not be saved and had to be amputated.

The tragedy was made public by Roman Galenkin, a 22-year-old municipal deputy for the Obruchevsky district and a member of the Russian Maoist Party. According to Galenkin, “after this horrific story, several employees resigned, unwilling to be part of what is happening within the walls of the social home.” However, the facility’s director, Alexander Bondar, who has held the post since May 2025, chose to remain silent.

Galenkin posted a video on his Telegram channel, recorded by Viktoriia’s fellow resident, Roza Fatykhova. According to her, when Viktoriia was admitted to the institution, she was “a neat girl with braids,” then she had her hair chopped off and was dressed in dirty clothes. Viktoriia did not speak, but she was not violent. Nevertheless, orderlies twisted her arms every day, tied her to a wheelchair, and left her like that in front of the television. In the evening, they tied her hands to the bed frame and left her to sleep in that position.

According to Fatykhova, taking advantage of the lack of cameras in the bathroom, orderlies dragged the girl by her hair and beat her, “because there is only one orderly taking care of so many people, and everyone’s diapers need to be changed.” This went on for the entire two years that Budkina and Fatykhova lived on the same floor.

“Tying people up is a classic human rights violation in psychiatric care homes,” psychologist and sociologist Leonid Tsoi, author of a study on Russia’s psycho-neurological residential facilities (commonly known under the abbreviation “PNIs”), told The Insider. “It is cruel treatment. In theory, tying alone is already punishable. Psychiatric institutions can use gentle restraint techniques with residents, but PNIs don’t even have the proper means for that. Some homes may have a few outdated straitjackets. Otherwise, they just use leggings, as they did in the case of this girl.”

As Tsoi explains, by law, a person in a psychotic state who may harm themselves or others should be hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital. However, these institutions are often overcrowded. Moreover, transferring a care home resident involves a number of bureaucratic procedures. Due to understaffing, proper help for such patients cannot be provided in psychiatric care homes either, so they are most often locked up or restrained.

Violations of patients’ rights at Obruchevsky have entered the public eye before. In the fall of 2022, a video emerged showing residents of the facility being forced to vote in the municipal elections for the then-director of the care home, Andrei Besshtanko, who ran as a candidate from the pro-government alliance “My District.”

“People were wheeled to the ballot boxes, and their hands were used to fill out ballots. If a person was unable to move their hands, they were shown how to mark Besshtanko’s name,” an eyewitness told The Insider. “The ‘voters’ could not move around on their own, barely moved at all, did not speak, and were unaware of what was happening around them.”

Care home residents were wheeled to the ballot boxes and shown how to mark their director’s name on a ballot

Election commission member and human rights activist Anastasiia Korenkova documented how care home staff showed a disabled man, who could not even hold a pen, how to mark a cross on the ballot. Korenkova managed to deprive Besshtanko of 12 votes that had been cast by people who were not participating in the election of their own free will.

In 2023, one of Obruchevsky’s legally incapacitated residents, 40-year-old Alexander Usov, took his own life. His friend recorded a video at Usov’s grave, accusing the administration of the social home of being responsible for his death. According to the friend, due to the administration’s negligence, residents of the facility had access to hard drugs. After using them, Usov began experiencing auditory hallucinations. Anton Cheltsov, who worked for several years as head of the legal department at Obruchevsky, said that Usov’s death was never investigated: “They just reported what happened. No one looked into why or under what circumstances it occurred.”

In early 2024, one of the care assistants died at her workplace, unable to cope with the excessive workload. The facility’s management claimed that the employee had died from alcoholism. According to Cheltsov, Obruchevsky staff were physically unable to handle such a large number of residents (one nurse for 60–70 patients) and were constantly overworked, while the administration's only concern was to cut costs wherever they could. As a member of the union committee, Cheltsov helped workers defend their rights until he was forced to resign (despite himself being a Group III disabled person).

In February of the same year, Elena M., a 48-year-old legally incapacitated resident of Obruchevsky, was hospitalized at the Sklifosovsky Research Institute Hospital with a fractured ribcage. The victim reported that a caregiver had beaten her in the women’s restroom. However, after requesting footage from the surveillance cameras, the police found no evidence to support her claims.

In the summer of 2025, director Besshtanko was replaced by Alexander Bondar, who had earlier spent two years as director of the Fili-Davydkovo social home. In an anonymous statement passed to Roman Galenkin, employees of that institution claimed that Bondar had appointed his friends, former colleagues, and relatives to leadership positions, despite their lack of proper qualifications. Meanwhile, longtime staff were pressured and threatened into resigning.

Moreover, Bondar himself lacked the necessary qualifications and did not have relevant professional education. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Physical Education and Swimming Instruction and a master’s degree in Public and Municipal Administration. Staff remember Bondar’s tenure for numerous financial violations and an outbreak of scabies. The latter occurred due to failure to follow quarantine protocols, affecting both residents and staff of the facility.

The staff remembered Bondar’s tenure for numerous financial violations and a scabies outbreak

“All such positions in Moscow are obtained solely through nepotism, via the Department of Labor and Social Protection,” says Nikolai (name changed for safety reasons), an activist promoting the campaign to reform Moscow’s psychiatric care homes. “The director of a social home earns more than 700,000 rubles a month [$8,950], deputies earn over 300,000 rubles [$3,830], but no experience or knowledge is required for these positions. Bondar, who had never worked in social care, immediately got the chance to run a facility. When he came to Obruchevsky, things got even worse. Under Besshtanko, the institution was more or less functional, but under Bondar, it turned into a real torture chamber.”

Among other things, under Bondar, the facility struggled to provide its residents with drinking water. Orderlies were forced to buy it with their own money or boil tap water.

Russia currently has more than 500 neuropsychiatric residential facilities, housing over 155,000 people. The vast majority of the residents have been declared legally incapacitated and are therefore deprived of all civil rights: the right to go to court, to marry, and to manage their own money. Seventy-five percent of their meager pensions is deducted to cover the cost of their stay in a care home, effectively returning the money to the state. The administration of each facility serves as the collective legal guardian of all residents and also controls all of their property.

The majority of these people have mental disorders of varying severity and therefore cannot fully function in society. However, a mentally healthy person can also end up in the care home system if they are suddenly left without care, were not taught to read in time, or were misdiagnosed at an early age (with an intellectual disability, for instance).

If parents abandon an infant who is found to have physical or neurological impairments, the child is placed in a baby home. They are then automatically transferred to a children’s residential care institution and from there to an adult care home for permanent residence.

“Those institutions mostly take in elderly people with health problems, including mental health issues. They are lonely seniors or people whose relatives can no longer support them,” explains Daniil (name changed for safety reasons), an activist promoting a reform of Moscow’s psychiatric care home. According to Daniil, the main categories of residents also include disabled people, especially those with severe mental illnesses, and children from dysfunctional families, such as those with alcoholic parents.

Human rights advocates argue that, wherever possible, residents of care homes should be moved to supported living in conditions closer to a domestic environment. In this model, they live in small groups in a dedicated house or training apartment, where a social worker helps them gradually acquire the skills needed for independent living. Discussions of such a reform began back in 2018; however, at the same time, Russian authorities were allocating tens of billions of rubles to build and renovate conventional psychiatric care homes designed to house hundreds of residents.

Human rights advocates argue for transferring care home residents to living arrangements closer to a domestic environment

When describing what the care home system looks like from the inside, Leonid Tsoi and Nikolai independently use the word “concentration camp.”

“This is not an insult, but a standard definition,” Tsoi says. “What is a concentration camp? It is an institution whose purpose is the isolation of people. In a hospital or prison, people are placed temporarily, after which they have the opportunity to return to society. A concentration camp, however, does not allow for an exit. People remain in a PNI until the end of their lives. It is very hard for outsiders to get in, and human rights activists and journalists are not too keen on going there.”

Tsoi had first-hand experience dealing with the system as a teacher at an art studio for residents of the PNI-3 care home in Saint Petersburg. During his time there, he witnessed all kinds of abuse and violence. One resident, artist Daniil Rekhtin, regularly showed up to his classes after having visibly been beaten. Later, Daniil was found dead (Tsoi is convinced he was beaten to death). Only after Daniil’s death and Tsoi’s own resignation was he able to have the care home director, Natalia Zelinskaia, removed from her position. However, Tsoi describes the changes that followed as “cosmetic.”

Residents of psychiatric care homes are arguably the most disenfranchised category of Russian citizens. They are routinely robbed, humiliated, subjected to forced sterilization, and made to work for free for participants in Putin's “special military operation” in Ukraine.

In 2023, seven people under the age of 25 died one after another at a psycho-neurological care home in Saint Petersburg. According to human rights advocates, the mass deaths were a predictable result of indifference toward the patients.

Tsoi says that psychiatric care homes not only fail to provide proper care, but that life in them is organized so that even the simplest daily needs cause pain and suffering. Feeding becomes a form of torture when soup and the main course are mixed on one plate and shoved down a patient’s throat while still hot. The person gags, tears stream from their eyes, but they are powerless to resist. These institutions very often lack adequate medical care, a problem worsened by the fact that patients cannot communicate their symptoms.

Feeding becomes a form of torture when soup and the main course are mixed on one plate and shoved down a patient’s throat while still hot

The only entertainment accessible to residents in most care homes is a television set in the hallway. Model facilities may offer a choice of hobby clubs or activity groups, but if attendance is not monitored, the responsible staff can go on tea breaks instead, leaving their charges to wander the halls or lie in bed, developing pressure sores.

“Another tragedy is that people with physical disabilities (mentally intact but confined to a bed or wheelchair) and physically able people in very severe mental states are housed together,” Tsoi says. “The latter steal from the former, appropriating their food and personal belongings from bedside tables. Not really stealing, just taking, because people in severe psychosis have no concept of ownership. Or they urinate on them — patients of the first category cannot move, yet they remain fully aware of everything happening around them.”

In the late 2010s and early 2020s, Russian artists and journalists repeatedly tried to draw attention to the inhumane conditions faced by residents of care homes. The Latitude and Longitude project, in which Leonid Tsoi participated, focused on finding self-taught artists and setting up art studios inside care homes. At the end of 2018, a picket took place in Moscow, joined by a care home resident from the Tula region.

The start of the full-scale war with Ukraine, which caused many activists to leave the country, dealt a blow to the fight for the rights of people with disabilities, just as it did to other forms of civic activism.

In September 2024, a controversial package of amendments to Russia’s Law on Psychiatric Care came into force despite opposition from dozens of specialized NGOs, which collected more than 40,000 signatures requesting that it be rejected. Instead of simplifying the process for a person to voluntarily leave a care home and facilitating the routine transfer of residents to home-based social care, as human rights advocates had hoped, the amendments created an additional bureaucratic barrier to discharging patients. Decisions on discharge must now be made by interagency commissions overseen by regional social protection authorities.

Notably, as The Insider’s sources point out, cases of discharge from care homes with restored legal capacity were already extremely rare. “In practice, we’re not talking about dozens, but a handful of cases nationwide,” says Tsoi. “The director of a care home in the Russian Far East, who had discharged several residents with full legal capacity, was fired. Around 2018, when talks of reform began, some people managed to regain limited legal capacity. This meant they received certain privileges compared to other care home residents — for example, the right to occasionally leave the premises and buy cigarettes. But this could hardly be called living a full life.”

The same amendments abolished the legal grounds for creating independent public agencies to protect the rights of people with mental disorders. At the time, Sergei Leonov, then deputy chair of the parliamentary Health Committee, explained that the provision had not been used for 30 years anyway.

Human rights advocates insisted that the provision should not have been abolished, but rather made functional. As a positive case, they cited the experience of the Service for the Protection of the Rights of PNI Residents, established in Nizhny Novgorod, which had successfully helped facility residents and even managed to get some people out of isolation.

According to The Insider’s interviewees, isolation cells are “prisons within concentration camps”: tiny rooms locked with an iron door and a barred window, containing nothing but a chamber pot and a bed. Care home residents can be kept there for more than a week for infractions as minor as saying something the staff did not like.

Care home residents can be locked up for a week just for saying something the staff did not like

In 2020, Moscow began reorganizing its psycho-neurological residential facilities into social homes. The rebranding, as city authorities explained, was meant to reflect a move away from the outdated concept of closed institutions “with strict supervision and discipline” toward one of “open and friendly social homes.” Residents were supposed to enjoy vast opportunities for an active life and self-realization.

According to Oksana Shalygina, deputy head of Moscow’s Department of Labor and Social Protection, a neuropsychiatric residential facility was supposed to become “a comfortable environment for living and working.” Other regions decided to follow the capital’s example. In the summer of 2024, the St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly decided to rename PNIs as social service homes, and a similar renaming will take place in the Volgograd region starting in January 2026.

“Medical care in these institutions was punitive and has remained so even after the renaming,” Nikolai comments. “The laws were written for appearances and do not work in practice. Everything that happens is just a show and a money grab. In some ways, it has even gotten worse, because there used to be more information about PNIs. The purpose of the renaming was precisely to camouflage this problem, at least to some extent. Regardless of any renaming, things similar to what happened to Viktoriia occur in other social homes in Moscow. As for what goes on outside the capital, I’m afraid to even imagine.”

The main way to participate in the lives of care home residents remains volunteering, a process facilitated by numerous charitable organizations. A volunteer spends only a few hours in the facility, but even that short time can be enough to make the atmosphere of the institution feel more humane.

However, Tsoi emphasizes that volunteers cannot engage in human rights work: “For obvious reasons, outsiders are not welcome there. You might be allowed in if you convince the administration that you want to do something harmless with the residents, like sculpting figurines or making soap. But under no circumstances should you say the word ‘rights’ — you’ll be out the door before the word leaves your mouth.”

A source also notes that those who come to social homes as volunteers may develop an idealized image of these institutions — one that does not fully reflect reality.

“It’s very important to understand that volunteering is coordinated with the administration, so you may not see the whole truth. You’ll visit at strictly designated times. They’ll give you the most active residents, willing to sculpt, dance, and sing songs. They’ll tell you how splendid they’re doing, and you’ll leave fully convinced that psychiatric care homes are paradise on earth. No volunteer in their right mind is ever allowed onto a closed floor [where residents in the most severe conditions are housed], or into isolation cells, or permitted to interact freely with residents.”

According to Tsoi, PNIs were designed in the 1950s as extremely closed, almost classified institutions. Care home buildings, on the other hand, were constructed according to 1970s designs and feature large areas that are inaccessible to outside visitors.

“When I was being dismissed, a prosecutor’s office employee came in and later said that he couldn’t find the ward where the deceased Daniil Rekhtin had lived,” Tsoi recalls. “I asked him, did you search on your own, or were you led around and shown? ‘Of course, we were led,’ he replied. Then I had to draw him a map, explaining that there are entire labyrinths, basements, places someone from the outside cannot possibly find. There’s also a terrible stench from people not being washed for months. In the men’s locked psychiatric wards, there’s horrific starvation: you walk in and see living skeletons, like in Auschwitz. They don’t see outsiders very often, so when you enter, they immediately swarm you, like Indians probably did when they first saw a white man.”

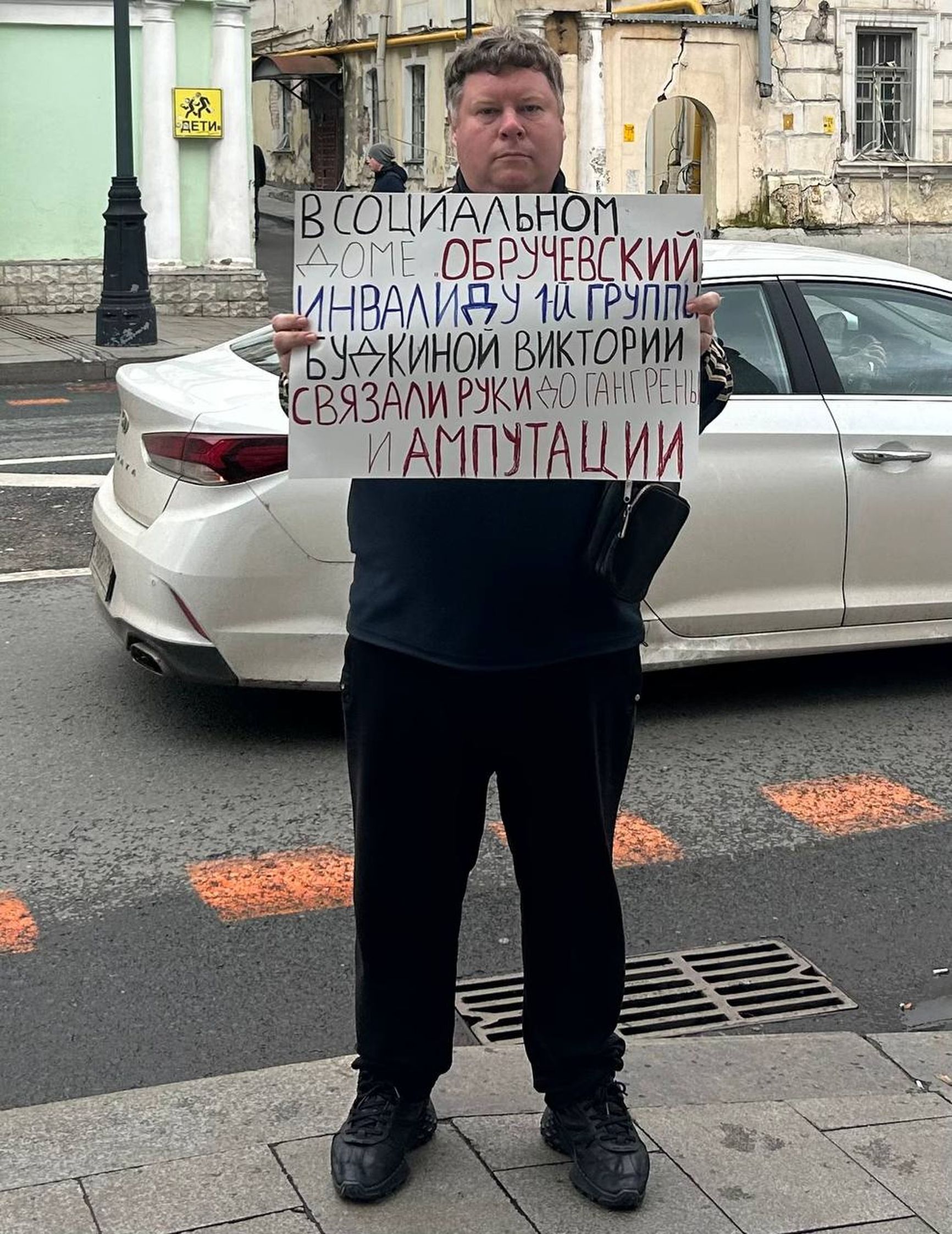

The horrific story that happened to Viktoriia would have likely gone unnoticed had it not been for the activists willing to help care home residents and defend their rights. On Oct. 29, Anton Cheltsov staged a solo picket in front of the Moscow Department of Labor and Social Protection, demanding accountability for those responsible for torturing the young woman. Roman Galenkin submitted a deputy’s appeal to the Investigative Committee. Activists wanted to draw the attention of the public and law enforcement in order to hold the entire leadership of the social home accountable, not just the people who physically tied the girl’s hands too tightly. “While it is clear that the direct perpetrators are guilty, none of this could have happened without negligence, nepotism, and professional incompetence,” a source explains.

The day after the picket, prosecutors visited Obruchevsky and questioned two orderlies, and the Investigative Committee opened a case under Article 218 of the Russian Criminal Code (causing grievous bodily harm by negligence). On the same day, Moscow’s Minister of Labor and Social Protection, Yevgeny Struzhak, visited Obruchevsky and announced the dismissal of director Bondar.

In addition to the director, the head of the medical service (Svetlana Kostina) and the chief nurse (Irina Andreeva) were also removed from their positions, with Roman Galenkin submitting a request to the prosecutor’s office to review the legality of their actions. Emergency repairs began at the care home, and old mattresses were hastily thrown out. Officials promised to organize a comprehensive habilitation program (developing new skills for people with disabilities) for the injured young woman.

“The incident made a big splash. The labor and health departments began inspections in social homes and psychiatric hospitals,” Nikolai says. “At the very least, managers and staff will now be more cautious, and the kind of negligence they previously hoped would go unnoticed will decrease. The very fact that this happened somehow mobilized people to take their work seriously.”

Activists have no intention of stopping. Roman Galenkin, Anton Cheltsov, Mytishchi municipal deputy Olesia Berg, and former employees of Moscow social homes published an appeal urging all care home staff, the relatives and guardians of residents, and concerned Russians, to break their silence about what happens in the institutions. They call on people to report all “cases of tying up, lack of care, lost pensions, epidemics, humiliations,” to document all violations with photos and videos, and to create an organized movement.

Activists believe that the entrenched “concentration camp” system in Russian care homes can be broken only through joint efforts by residents, sympathetic staff, and relatives or guardians. But Russian civil society must also show solidarity.

In social homes with an independent union branch, defending the rights of both staff and residents is easier, notes activist Daniil. Violence does not arise on its own: it is the result of underfunding in the healthcare system and resulting staff shortages. When proper working conditions are created — when employees are not constantly overworked and do not fear for their positions — there is no reason for personnel to treat patients with hostility.

When employees are not constantly overworked, there is no reason to treat patients with hostility

According to the volunteer, the war in Ukraine has had a profound negative impact on the situation, further straining the meager funding allocated to civilian healthcare. In addition, the very culture of aggression, violence, and cruelty has now become a state policy: “The administrators have become more aggressive, and this inevitably affects the residents. The case with Viktoriia was so egregious that even pro-government media and officials could not ignore it. However, hers is just one of thousands of horrific stories.”

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari