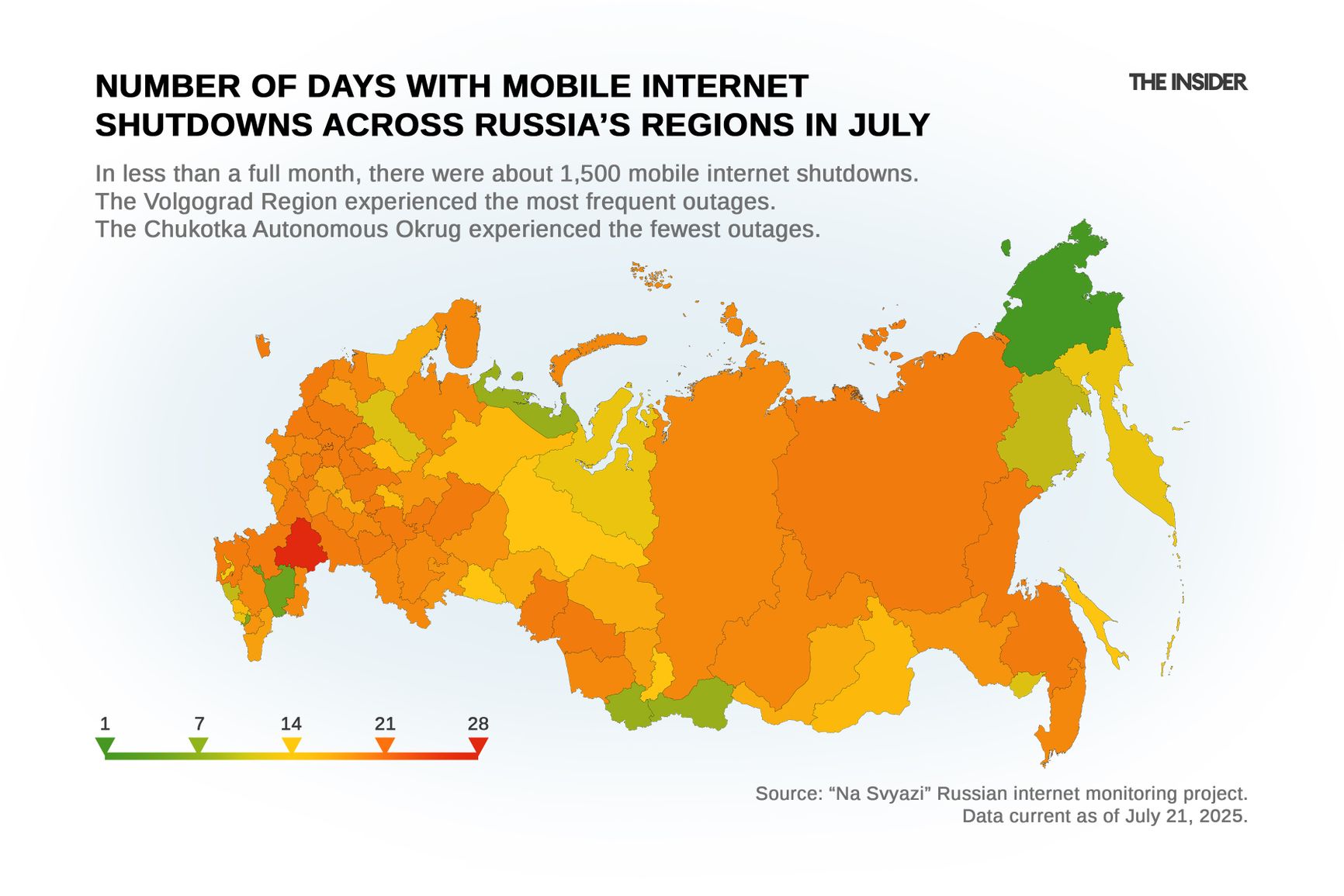

Since May, mobile internet disruptions across Russia have surged, with June breaking the world record for the highest number of shutdowns in a single month. According to the watchdog group Na Svyazi (lit. “Stay in Touch”), Russia logged more than 1,470 outages in July. What began as sporadic outages has now become an almost daily occurrence in some regions. While Russian government officials describe the blackouts as “temporary measures” undertaken in the interest of public safety — particularly to counter drone threats — many residents say they’ve been left without reliable service for weeks. As a result, people are reverting to offline routines: making phone calls instead of messaging, using cash instead of digital payments, and navigating daily life without apps.

Content

Why is the Internet being shut down in Russia?

How are people in Russia living without the Internet?

Why is the Internet being shut down in Russia?

The wave of shutdowns began during the May holidays, when mobile internet access was restricted in 40 regions. Residents reported dramatic drops in data speed — or even the complete loss of service. Delivery apps, taxis, car-sharing services, and the Central Bank's SBP money transfer system were all disrupted. In some cities, even retail payment terminals stopped working. Alexander, a resident of Kaluga, recalled:

“During the holidays, mobile internet didn’t work at all, [there were] only calls and text messages. A lot of payment terminals rely on mobile data, so many cafés stopped accepting cards.”

Olga, from Moscow, had a similar experience: “I couldn’t pay with a QR code or money transfer. Everyone was asking for cash. One supermarket employee gave me their Wi-Fi password so I could pay.”

![Barricades and blocked streets in central Moscow during the May holiday period. A banner in the center reads "[We are] proud of [our] Victory! 1945-2025."](/images/qxV4TfJv5dErZmdQJNnUhNZR9056NqMSBY2TjlW-t2A/rs:fit:866:0:0:0/dpr:2/q:80/bG9jYWw6L3B1Ymxp/Yy9zdG9yYWdlL2Nv/bnRlbnRfYmxvY2sv/aW1hZ2UvMzYxNzYv/ZmlsZS0wYWViODVj/MDQ2N2U5NWZkODAy/ZWVjNWJmOGQ4NzRk/Yy5qcGc.jpg)

Barricades and blocked streets in central Moscow during the May holiday period. A banner in the center reads "[We are] proud of [our] Victory! 1945-2025."

Photo: The Insider

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov justified the restrictions by blaming a “dangerous neighbor” — a clear reference to Ukrainian drone attacks — and asked the public to respond to the disruptions with “understanding.” Peskov’s commentary notably eschewed the reciprocal nature of the ongoing drone war. For example, on the night of May 18, Russia launched a record number of drones against Ukrainian territory, and then, from May 20-23, Ukraine retaliated with its largest aerial assault in the four years of the invasion, launching more than 1,000 drones of its own.

Following these events, Russian authorities began jamming mobile internet across various regions — no longer just during holidays or mass gatherings (1, 2).

But the situation significantly escalated in early June following Kyiv’s successful Operation Spiderweb, in which Ukrainian drones attacked four strategic airbases in Russia’s Irkutsk, Murmansk, Ivanovo, and Ryazan regions, damaging more than 20 Russian aircraft. That operation, according to Mikhail Klimarev, head of the Internet Protection Society, served as the impetus for a more aggressive domestic shutdown strategy:

“A few days after the operation, they started cutting mobile internet. They assumed Ukrainians were guiding drones via mobile networks — which is not true. There’s barely any mobile service on military airfields. These shutdowns are based on a misunderstanding of how drones work. But more importantly, it’s the only method authorities have found to counter drones. They cut the internet, and the drone didn’t come. Maybe the drone wasn’t coming anyway, but they locked onto the idea that this worked — and decided they’d found a solution.”

As a result, the shutdowns became so widespread that the number of local outages in June broke a global record. According to data from the Russian internet monitoring project Na Svyazi (“Stay in Touch”), the regions with the highest number of mobile internet blackouts were Omsk (20 shutdowns), Pskov (19), Saratov (18), Rostov (17) and Nizhny Novgorod (also 17).

The scale of shutdowns in Russa became so widespread that the number of local outages in June broke a global record.

The process of shutting down the internet is relatively simple: mobile internet is jammed through traffic filtering equipment known as “TSPU” (an abbreviation for “Technical Means to Counter Threats”) or it is throttled directly by mobile operators, who reduce data speeds. According to the Internet Protection Society’s Klimarev, the implementation varies widely from region to region, with decisions largely left to local authorities:

“Based on the documents I’ve seen, here’s how it typically happens: either the regional emergency headquarters declares a ‘drone threat’ and sends letters to mobile operators demanding that mobile internet be shut down within a specific region or administrative district, or the shutdown is carried out through the TSPU — by blocking the IP addresses of cellular base stations.”

Frequently, disruptions affect only some of the operators in a given area. For example, T2 users may lose access, while MTS continues to function normally. Klimarev attributes this to human error and operator discretion. “One operator may have missed the notice and didn’t shut down in time. Another might have decided, more boldly, to gain a competitive edge by staying online. Others might have simply executed the shutdown incorrectly.”

Local officials themselves often don’t know how long a shutdown will last, nor how to explain the situation to the public. Vitaly Matyukha, head of the Usolsky District in Irkutsk Region, said the restrictions were being implemented “for safety reasons” and asked residents to be understanding. Saratov Region Governor Roman Busargin stressed the “temporary nature” of the disruptions. In the Omsk Region, where mobile internet has been unavailable since early June, Governor Vitaly Khotsenko has changed his explanation multiple times, citing “scheduled maintenance” on one occasion and “security concerns” on another (1,2).

On July 21, the Operational Headquarters of Altai Krai offered a new rationale, stating that the disruptions were due to “enhanced security measures at administrative, logistics, and industrial sites.” Officials in the Sakhalin Region, meanwhile, cited a broad telecommunications system inspection program.

The chaotic nature of the shutdowns can be traced to the large number of different bodies authorized to issue restriction orders, the Na Svyazi monitoring project explained. “Right now, orders can come from practically anyone — the city mayor, the regional governor, the local Emergency Ministry — anyone who suspects internet access should be restricted. Operators comply with the shutdown orders, but there’s no clear guidance on when to restore service. Authorities are now discussing the creation of a centralized body to regulate these shutdowns, because the consequences are becoming impossible to ignore.”

Since the end of June, disruptions have begun affecting not just mobile but also wired internet in several regions — a sign, analysts fear, that authorities may be preparing for broader and longer-term restrictions.

“It looks like a kind of psychological conditioning,” noted analysts from Na Svyazi. “Yes, the situation is dangerous, but also convenient. Being offline is becoming routine. And once the drone threat subsides, people may no longer react strongly to future internet restrictions.”

According to the project’s estimates, mobile internet was shut down at least 1,470 times in July — more than doubling the previous monthly record of 655.

How are people in Russia living without the Internet?

The impact of internet shutdowns has become increasingly noticeable. Most significantly, the constant disruptions have affected businesses.

“People are practically losing their ability to earn a living,” reports Na Svyazi. “For example, if the owner of a grocery store doesn’t have a wired internet connection, they can’t accept card payments. And wired internet is often unavailable even in major cities, because internet service for legal entities is more expensive. Not every business can afford to spend 100,000 rubles ($1,250) to install a cable.”

More importantly, there are places where everything — from services to sales — is completely dependent on mobile internet being available:

“In small towns, people use USB modems not just at home, but in offices too. They even run small-scale production through modems. And now they’re [left] completely without [the] internet,” the project notes.

Taxi and delivery services have also been hit hard. Not all of them are able to accept orders without internet access, let alone to reach the requested destination. “Taxi drivers, for example, have to take orders wherever there’s Wi-Fi, then drive passengers the old-fashioned way — using paper maps,” the team says. Still, people are adapting to the new reality.

Taxi drivers have to take orders wherever there’s Wi-Fi, then drive passengers the old-fashioned way — using paper maps.

Anna, from Voronezh, even sees certain positives in the situation:

“We actually kind of enjoy this forced digital detox. The level of human interaction has grown a lot. Like, people will cover each other’s bus fares, for example. And I’ve started talking on the phone more — I’ve always preferred that kind of communication; it’s faster and more convenient. I wouldn’t say that not having internet really throws off my life. If someone urgently needs me, they’ll call.”

Mobile internet shutdowns in the Voronezh region began as early as May. Initially, authorities spoke of “restricted” connectivity in “certain areas,” particularly during holidays and mass events. But starting in June, the number of shutdowns sharply increased. Analysts from Na Svyazi counted 12 shutdowns in June and 21 more in the first three weeks of July alone.

I’ve started talking on the phone more — it’s faster and more convenient.

According to Anna, the greatest difficulties arise when it comes to transportation:

“You can only plan a route from home, and taxis are the biggest headache. This past weekend I booked a ride from my home Wi-Fi. I took my family outside and noticed after 10 minutes that no car had arrived. I stood under the windows trying to catch a signal — finally got one and saw that the driver had canceled the ride. Then I had to call another one, explain where we were standing, wait for him to arrive — that whole thing took 40 minutes. And I still had multiple stops across town. It was just too much.”

She shares another story:

“Not long ago I was in a residential neighborhood and asked a guy for directions — he pulled out a paper map and looked it up. I wonder if demand for those has gone up at bookstores.”

Navigation is not the only area where the shutdowns have caused Anna real inconvenience. Making card payments or money transfers in small shops and salons has also become difficult:

“If terminals run on SIM cards, they get cut off. And we always used to pay with QR codes, because taxes are high. For manicurists, we’d usually send money through Sberbank. My manicurist and my hairdresser both said right away: ‘Bring cash.’ And I get it, what would we do if she finishes my pedicure and I have no internet, and she only has Wi-Fi?”

At the end of June, some stores in Voronezh couldn’t sell certain products even for cash. The issue was mandatory digital labeling: goods like milk, water, beer, and cigarettes must be verified through the “Chestny Znak” (“Honest Sign”) tracking system, which won’t update without an internet connection.

As analysts from Na Svyazi note: “If a store’s terminal is connected via mobile internet, the Chestny Znak system also automatically stops working, and people can’t buy a large number of basic food products. And while you can do without beer, you can’t really do without milk or water.”

Medications are also subject to mandatory digital labeling, and as a result, many small regional pharmacies have had to shut down due to a lack of mobile internet. Although representatives of the Chestny Znak system have claimed that there shouldn’t be any issues, pharmacies continue to report failures in the sales system.

Many small regional pharmacies have had to shut down due to a lack of mobile internet.

Surprisingly, when connections suddenly drop, Wi-Fi in public places has often come to the rescue for locals in Voronezh.

“Supermarkets like [alcohol retailer] Krasnoe & Beloe or [major nationwide chain] Pyaterochka are now offering public Wi-Fi. For couriers and taxi drivers, that’s almost the only way to start a shift. Drivers use it to catch a ride: they’ll call you to say where to wait, drive to your location, and then follow your directions. After that, they’ll head back to a place like McDonald’s or Pyaterochka to get their next order,” Anna explains.

Some cafes and restaurants also offer free Wi-Fi access: “They put up signs near the entrance like ‘Internet Available Here,’ and that can help when you really need it,” she adds.

A coffeehouse chain advertising its Wi-Fi access point in Voronezh, Russia.

Photo: Anna, Voronezh

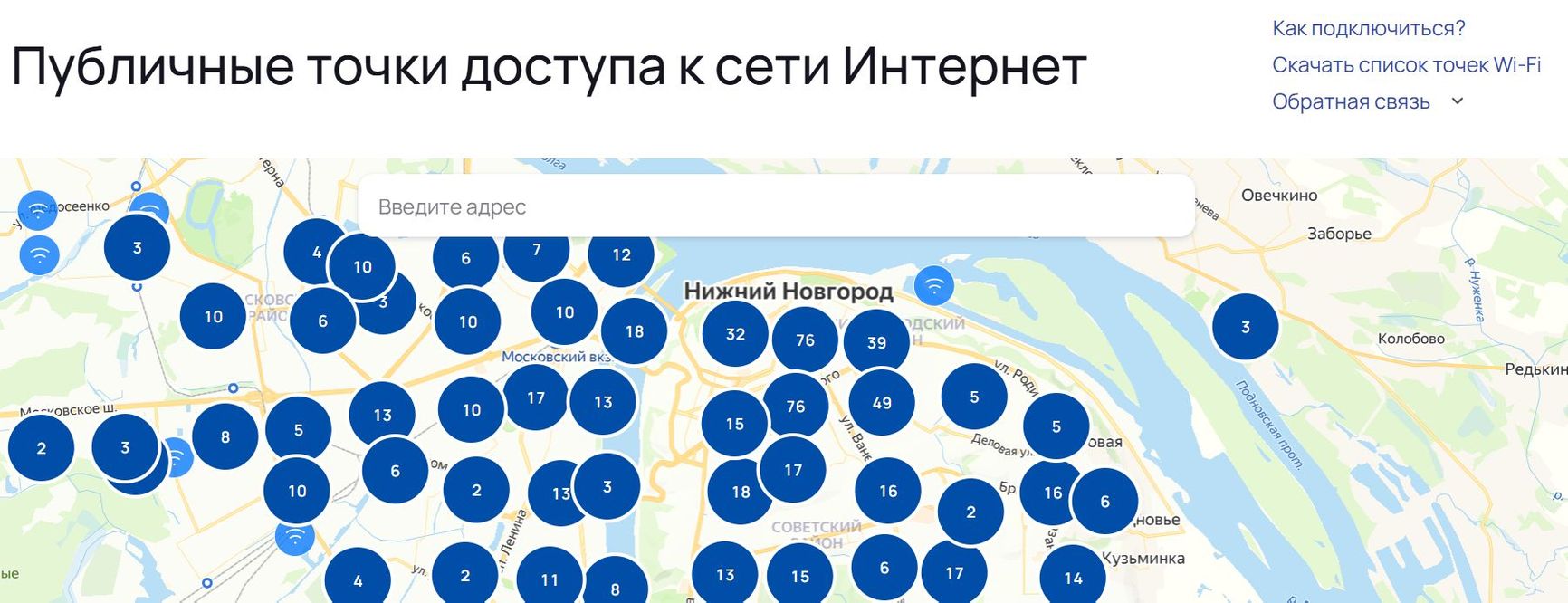

Wi-Fi hotspots like those in Voronezh have started appearing in cities like Nizhny Novgorod as well. In June, mobile internet was shut down 17 times in the region; In the first three weeks of July, the count was 21.

According to Natalia, a resident of the city, taxi services in the Zarechnaya part of town can only operate with the help of these hotspots: “We now have free Wi-Fi points at ‘smart’ bus stops. That’s where drivers wait to get orders. We haven’t had to call a cab by phone yet, but we have started withdrawing more cash, as some card terminals in stores aren’t working.”

A map of free Wi-Fi access points in the Nizhny Novgorod Region.

A Voronezh resident named Kirill agreed that the service sector in the city has been hit hard in recent months, adding that some delivery services were down, in addition to payment issues at gas stations:

“We often use [online delivery service] Samokat, but lately they’ve completely stopped delivering. It’s also become harder to refuel: I like using Yandex Fuel, but when the network goes down, it becomes impossible — you have to go inside and pay at the register. In June, I ran into situations multiple times where the payment terminal at the station didn’t work. Maybe they've fixed it by now. I haven’t run into it recently.”

As for navigation problems, Kirill says they affect him less because he knows the city well:

“I know the city well, I can drive without a navigator. And if I need to go somewhere new, I use Yandex Maps like a regular map — just plot out the route point by point without relying on real-time GPS. So that’s not really a problem either.”

According to Kirill, there are days when the internet is completely down, and he has to call or text to make plans or contact people: “The biggest issue for me is communicating with my wife. But we found a workaround, we're back to good old text messages. And if I’m at home, I don’t really notice the outages because the Wi-Fi is stable.”

In St. Petersburg, the most serious blackouts occurred during the city’s International Economic Forum (June 18–21) and on the night of the “Scarlet Sails” graduation celebration (June 28). At the time, the local Committee on Informatization and Communications announced a “temporary slowdown in cellular data speeds.”

Throughout the month, intermittent internet disruptions of varying severity were reported across the city. The Na Svyazi project recorded 13 shutdowns in June and 21 by July 21. One of the most serious occurred in early July, when many residents reported a complete loss of connection.

“I’ve noticed that for the second weekend in a row, the internet hasn’t worked,” said Alexandra, a St. Petersburg resident. “While the disruptions on June 28–29 were more temporary — not everywhere, not for everyone, and varied depending on the provider — the situation on July 5–6 was much worse. For example, in the Primorsky district, there was no mobile internet from T2 starting around 1 p.m. until late evening on both Saturday and Sunday.”

According to Alexandra, such shutdowns automatically paralyze many delivery and taxi services, as well as payment systems in supermarkets:

“The stores only accepted cash. On Sunday, I forgot to withdraw any, and I saw people abandon their full carts and baskets of groceries near the exits and just leave — you couldn’t pay with a QR code or a bank card. The only line in the entire store was at the one checkout that accepted cash, if you were lucky enough to have it. It was the same on Saturday night. But that was at ‘Magnit.’ It’s possible that other stores didn’t see the same kind of meltdown.”

People abandoned their full carts and baskets of groceries near the exits and just left — you couldn’t pay with a QR code or a bank card.

She also emphasized how the lack of internet has had a direct impact on her work:

“I don’t know how others manage, but my job would have collapsed if it hadn’t been the weekend, [as] I rely entirely on mobile internet. Sure, I can work in Photoshop without the internet, but how do I get my assignment? How do I send the finished file?”

Elena, another resident of the city, says the connection issues affect her physical workplace, too. “At our office in the Krasnogvardeysky district, mobile service is nearly nonexistent. MegaFon and MTS don’t work — only Beeline or T2 do. So the poor couriers are often stuck,” she said.

St. Petersburg

The situation is even more dire in the Omsk Region, which recorded some of the highest numbers of shutdowns: 20 in June and 21 in July. Olga, a local resident, says mobile internet is almost completely unavailable. The first blackouts began on June 6, and since then, access has returned only intermittently, disappearing again after a few days.

“A cycling event was planned in the city center on June 7. My friends and I assumed the shutdown was connected to that public event — as it’s known that other regions have taken similar steps — but the weekend passed, and the internet still didn’t come back,” she said.

According to Olga, internet access has become like a lottery:

“Every day, a different provider might go offline. Some days it’s mobile internet, other days it’s home broadband. For example, you might lose mobile service for several days but still have Wi-Fi — and then they’ll switch places. One part of the city might have internet while another doesn’t. In the evenings, the connection often slows down so much that it becomes unusable.”

As elsewhere, this directly impacts basic services:

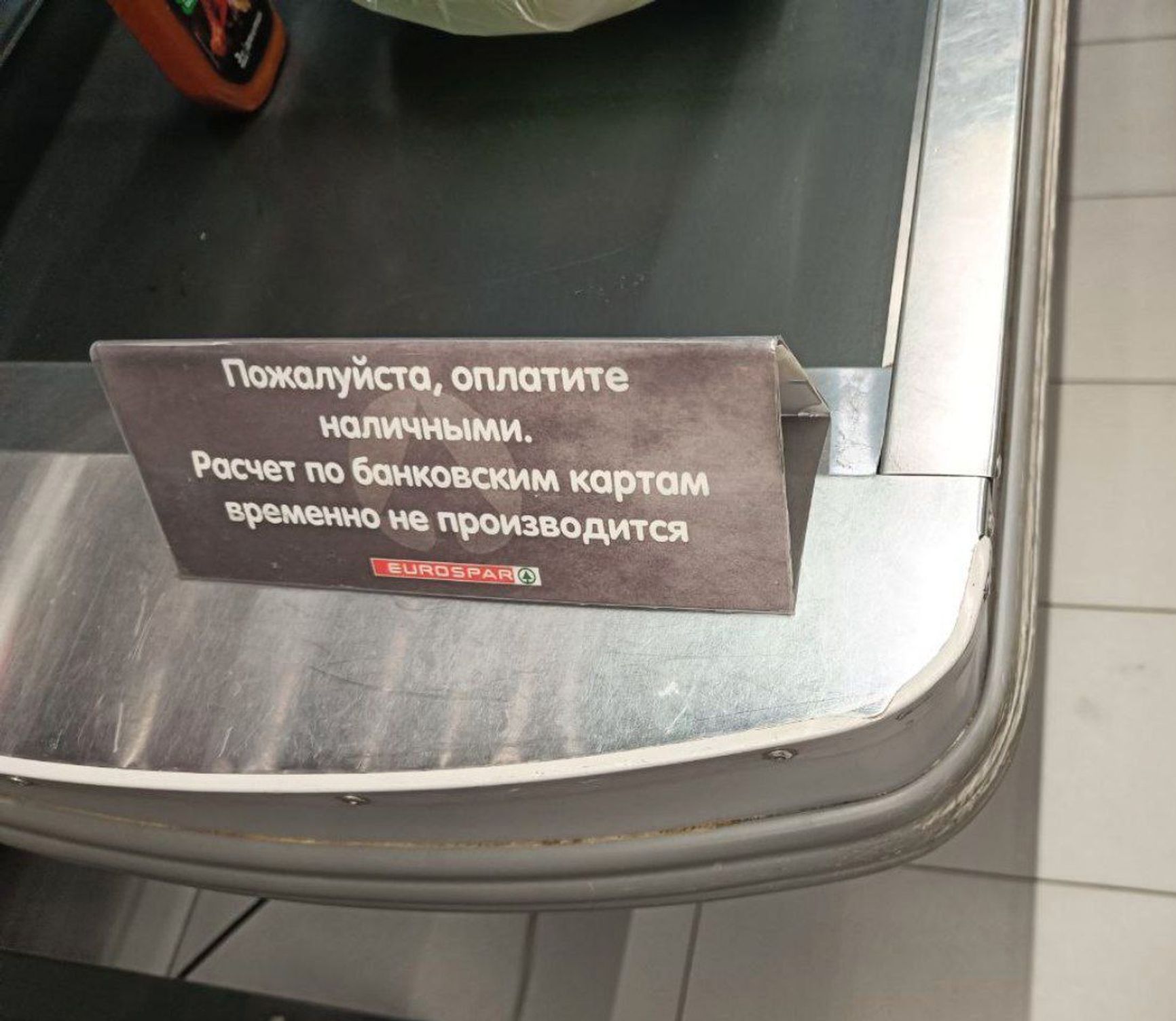

“If you don’t have internet, all the related apps won’t work either. You can’t hail a cab, order groceries, contact loved ones, or make payments using the SBP system. Even if everything appears to be working, there’s still a chance that you won’t be able to pay by card in some stores or buy items that require digital labeling through Chestny Znak, so we carry cash with us at all times.”

A sign at a checkout counter at the EUROSPAR supermarket chain reads “Please pay in cash. Bank card transactions are temporarily unavailable.”

Photo: Olga, Omsk

Olga adds that the constant lack of connectivity has led to growing anxiety: “The longer you’re offline, the more uneasy you feel, especially when neither officials nor telecom providers give a clear reason or timeline for when service will resume.”

Service disruptions have also been reported by Daniil, a member of the Omsk Civil Association who frequently receives complaints from residents: “Taxi prices have skyrocketed because drivers rely on mobile internet. Many can’t work now, so there are fewer cars available. A trip across town can now cost up to 1,000 rubles ($12.50) — which is unheard of for Omsk.”

Daniil says full blackouts are common near facilities connected to the military-industrial complex:

“They’re putting up signal jammers around those areas. Apparently, they’re afraid of drone strikes like the Spiderweb one. We’ve been receiving more reports that while the internet might work in some neighborhoods, it’s completely jammed near factories. In July, residents were even banned from bringing GPS trackers or phones near those sites.”

The use of cash is also on the rise in the Vladimir Region. According to Na Svyazi, the town of Kovrov saw 12 shutdowns in June and 21 more in July. Sergey, a local resident, says stable internet has been absent for nearly two months.

“In Kovrov, the internet only works through Wi-Fi. MegaFon and T2 don’t work at all. Stores have switched to cash, but salaries are still paid out to cards. It’s not ideal. I try to shop at Pyaterochka, since they still accept cards, and I order everything else from [online e-commerce platform] Ozon,” he said.

“Stores have switched to cash, but salaries are still paid out to cards.”

Cashless payments and online transfers are also proving difficult in the Rostov region, where mobile internet was shut down 17 times in June and 21 times in July. “Even before all this, our local market operated on cash,” said Dmitry, a resident of the Kamensky District. “But you could still pay a vendor by sending money to their card using their phone number. Now I have to send the money to the potato seller two or three times instead of once — and wait for it to go through.”

Unsurprisingly, taking a taxi has also become a hassle. “We don’t rely on mobile internet at all, but Wi-Fi always saves us. I often move from one Wi-Fi zone to another. For example, I hail taxis from cafés, because every decent café has Wi-Fi. But when there’s no Wi-Fi, I even call Yandex Taxi through an ordinary phone and an operator, just like in the old days.”

“When there’s no Wi-Fi, I call taxis through an operator, just like in the old days.”

Taxi drivers keep multiple SIM cards on hand, Dmitry noted. “If MTS isn’t working, then Beeline, T2, or MegaFon usually are. Two phones, two SIMs — that’s how everyone drives now.”

For regular communication, they just make calls:

“My wife called me today and said, ‘The internet’s down. I’m near Magnit. Do you need anything?’ She just used regular voice service, and I told her to get bread, matsoni, and sausage.”

In the Tver Region, residents are facing similar payment problems. The region experienced 15 internet shutdowns in June and 21 in July. “Sometimes we go without the internet for several days. In many stores, card payments and SBP transfers stop working, so we carry cash. Even the ATMs go down,” said Tver resident Pyotr.

According to him, such issues arise in small local shops and large chains alike. But taxi drivers and couriers are hit the hardest:

“Taxi fares in Tver have shot up. Navigation doesn’t work consistently, so drivers have to rely on memory to find streets. It’s especially tough for migrant drivers, which is why fewer of them are out. And prices are rising.”

Tver

Alongside internet shutdowns, Russian authorities have also frequently jammed geolocation services, making it even more difficult to get around. Olga, a resident of Moscow, said GPS disruptions in the city center began in spring 2022 and have only intensified since:

“The zone keeps changing. Sometimes it expands, sometimes it shrinks. For example, a friend was coming to visit but arrived over an hour late because her internet stopped working. The GPS didn’t work, and the map wouldn’t load. In the end, she left her car in my courtyard and took the metro home. And when GPS fails in our neighborhood, it always shows we’re in the middle of the Zhabenka River. My kid finds that hilarious.”

Despite the frustration, Olga said people are gradually adjusting. “Many are starting to treat this like just another daily inconvenience to live with. Personally, I feel conflicted: on the one hand, it’s better than having a drone crash into your building. For example, my sister lives in a residential complex in Dolgoprudny, and it was hit — she was terrified. But on the other hand, we can’t ignore what — or who — is really behind all this.”