Even before the current wave of protests began sweeping over Iran, the authorities in Tehran were already loosening their control over a few select aspects of everyday life in the country. Rules around the hijab were largely going unenforced, women could be seen riding motorcycles, and restaurants were discreetly serving alcohol. However, at the same time state control in the social sphere was on the wane, repression elsewhere was ramping up. Executions are on the rise, Nobel laureate Narges Mohammadi was recently beaten viciously during a protest, and a wave of spy mania is sweeping the country.

Content

Glimmers of liberalization

New record in executions

Economy and water

New war on the horizon

Sakhar (name changed) leaves her apartment in eastern Tehran and heads to work. It takes her about an hour to get to the university where she is listed as a research fellow — 20 minutes on the “express bus,” around half an hour on the metro, and finally a short walk.

“I always go out without a headscarf. It’s my principled stance ever since the Woman, Life, Freedom protests began,” Sakhar tells The Insider.

However, she still has to put on a headscarf when entering the university: “The dress code in educational institutions, as in offices, hasn’t been canceled; an officer at the entrance always checks.” Still, Sakhar makes a point of going everywhere else with her head uncovered.

According to her, things have indeed changed. “In the past year or two, the police no longer grabbed or detained anyone, but they might approach and give a warning,” she explains. “They would come up to me on the street, and at the metro entrance as well: a woman in a chador would be there, asking everyone without a headscarf to cover their heads.”

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Last year, the police no longer detained women with uncovered heads, but they would still approach and give a warning

Neither Sakhar nor any of her acquaintances has been fined in the past three years, despite receiving multiple texts with warnings about possible fines. “The most surprising case happened to my friend in Isfahan. She simply went out onto Naqsh-e Jahan Square with her head uncovered. Then she returned to Tehran, and an SMS warning arrived. Apparently, a smart camera recognized her face.”

But this year, the situation has changed even more: neither the police nor the Basij even give warnings anymore. “Outside office spaces, you can freely go out without headscarves. We’ve won this right back,” Sakhar says.

Glimmers of liberalization

A motorcycle crashes into a café in Isfahan through the front door, knocking over a couple of chairs and a table where patrons are sitting. Fortunately, there are no casualties. A camera captures the entire commotion. As people gather around the culprit, it turns out that the rider of the “motor” (as motorcycles are called in Persian) is a woman. Just a couple of years ago, this would have been almost unimaginable: women in Iran are allowed to drive cars, but not motorcycles.

Formally, the situation is exactly the same as with the hijab. Iranian women are still officially prohibited from riding motorcycles. But in practice, more and more women are getting on motorcycles, and the police do not interfere. Numerous videos have appeared online showing women holding motorcycle rallies. And, of course, all of them ride without licenses, given that they are still not allowed to obtain one.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Despite the ban, more and more women are getting on motorcycles in Iran, and the police do not interfere

In other words, Iran is undergoing a behavioral shift that is affecting both ordinary citizens and law enforcement officers. Legally, nothing has changed regarding the Islamic dress code: women are still required to cover their heads, arms up to the wrists, and legs down to the ankles. Moreover, last year the Iranian parliament, the Majlis, passed a law significantly tightening the penalties for violating these rules. A first dress code offense carries a fine, while a repeat violation can result in imprisonment from six months to three years.

However, at the end of 2024, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian suspended the enforcement of this law, citing “public dissatisfaction” while calling it “unjust.” Pezeshkian could not have taken such a serious step without coordinating the matter with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

This move is indicative of the current state of Iranian governance, which has suffered a prolonged crisis of legitimacy ever since the protests of late 2022. Moreover, the Islamic Republic would not want to antagonize its people amid a military conflict with Israel. Nevertheless, the new hijab law has been formally suspended but not repealed.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The system is trying to emerge from the prolonged legitimacy crisis exposed by the late-2022 protests

“True, we can go out without a headscarf, but I’m still afraid, because the law hasn’t been repealed — it's just that the police aren’t bothering anyone for now,” Parvane (name changed), a dentist from Tehran, says. “Since there’s no official repeal, [the enforcement] could come back at any moment.”

Another sign of change comes via reports that more and more Iranians are consuming alcohol openly. This past September, authorities announced the closure of a restaurant in one of Tehran’s public parks, where alcohol was “served regularly” and “dancing was performed.” But, in a way, this is good news given that such a place could be open at all.

Iranian law prohibits not only the sale but also the consumption of alcoholic beverages — an offense punishable by several dozen lashes. Mixed dancing of men and women in public is also banned. Just a couple of years ago, it would have been hard to imagine anyone consuming alcohol in a park in the capital, let alone that the restaurant owners would get away with just a closure following such an offense.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

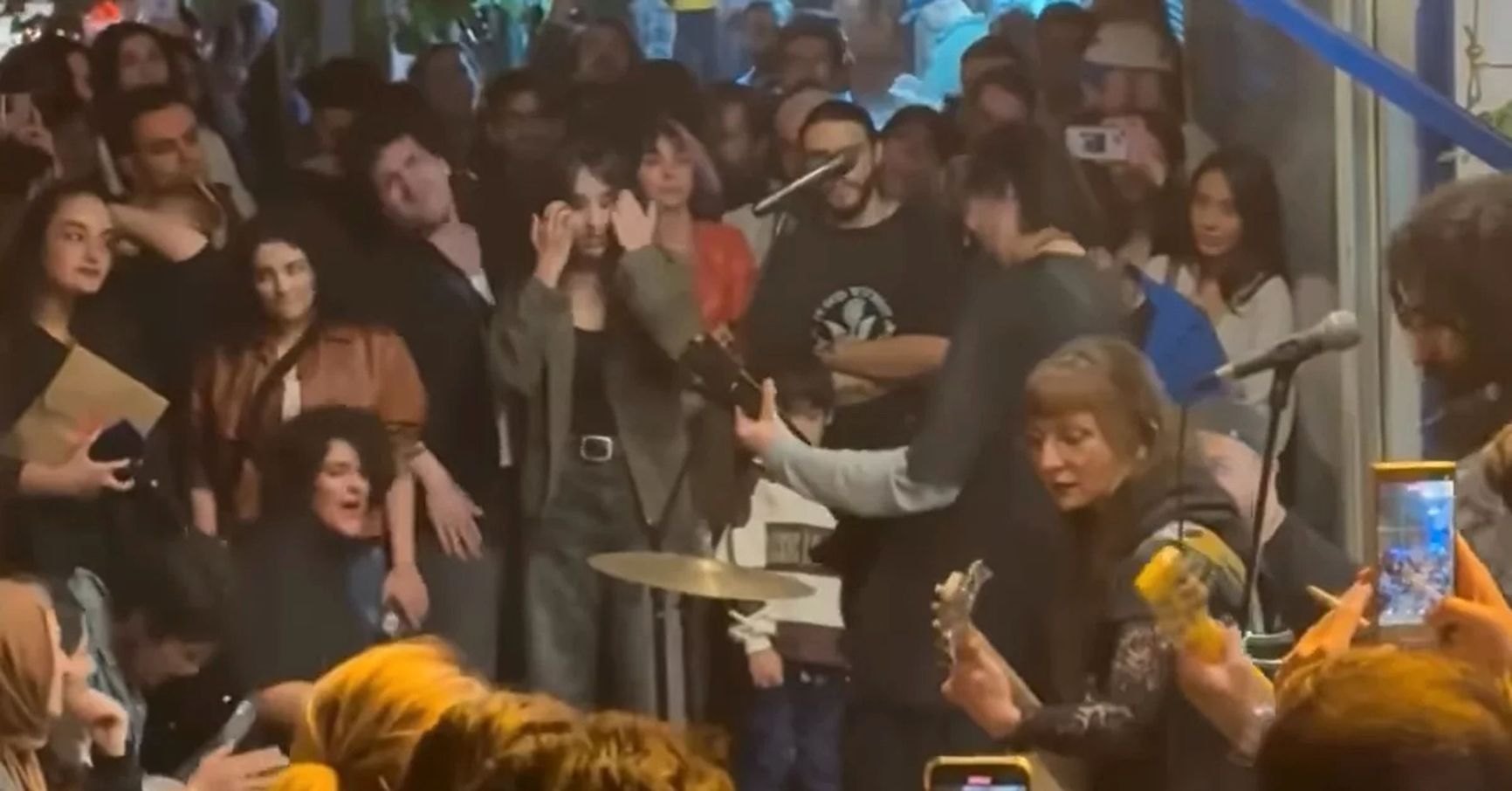

Rock music is banned in Iran, but even street concerts take place in major cities

Moreover, the case of the park restaurant was not an isolated incident. In November the head of Iranian police, Ahmad-Reza Radan, issued an address saying that public spaces “should not be filled with sin” and that restaurants serving alcohol should be sealed for several months.

Again, this is an indication that the “problem” extended well beyond the closed cafe in the park. Despite the harsh rhetoric, the very idea that serving alcohol now results not in lashes or imprisonment but only in loss of income represents unprecedented liberalization by Iranian standards. In major cities, semi-underground — and sometimes even outdoor — concerts of Western music take place, despite official rhetoric that labels such forms of entertainment “corrupting.”

New record in executions

Unfortunately, stories of relaxation in Iran are less encouraging when viewed in a broader context. Formally, 2023 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi has been serving a 13-year prison sentence since 2021 — jailed for “propaganda against the state” and “conspiracy against national security” — but thanks to a health-related temporary release, Mohammadi was able to participate in an event commemorating lawyer and human rights activist Khosrow Alikordi. However, at the memorial event in the city of Mashhad, around 15 plainclothes Iranian security personnel, who knew exactly who they were dealing with, beat her with fists, feet, and batons, then detained her yet again.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

In 2023, Narges Mohammadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for defending women’s rights in Iran

Still, a more objective indicator than the occasional high-profile act of violence is the rise in executions that began under the regime of conservative president Ebrahim Raisi (2021-2024). During the presidency of reformist Hassan Rouhani (2013–2021), Iran executed an average of 250–300 people per year. In 2022, however, according to Iran Human Rights (IHR), at least 582 executions were carried out.

In May 2024, Raisi died in a helicopter crash, and the following presidential election was won by reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, considered a liberal by Iranian standards. However, the number of executions in the country continued to rise. According to human rights activists, at least 1,000 people were executed in Iran in the first ten months of 2025.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

At least 1,000 people were executed in Iran in the first ten months of 2025

Notably, from a legal standpoint, the issue of executions is somewhat reminiscent of the hijab situation. While the legal framework has hardly changed over these years, the shift in law enforcement practice has been considerable. About half of all death sentences are handed down for drug possession or trafficking, with retribution-based executions, usually in cases of murder, serving as another major source of capital verdicts. Third are executions for rape.

Executions for national security-related cases make up only a small fraction of the total, mostly involving “crimes against the state or religion,” which primarily include those accused of “blasphemy” — as in the case of rapper Tataloo. Such cases usually number around 10–20 a year, meaning that while political repression is certainly on the rise, it is mainly not dissidents who have suffered most from the rise in executions.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Rapper Tataloo, sentenced to death in Iran

The conservative segment of the elite, which secured victory over the reformists in 2021–2022, sees executions as a normal way of interacting with society. The return of a nominal reformist to the cabinet has not changed this situation so far.

In addition to continuing the rising trend in the number of executions, 2025 introduced a new mode of societal pressure: spy mania, stemming from the 12-day war with Israel (and the U.S.) this past June. According to official data, since mid-summer around 21,000 people have been detained on suspicion of having ties with foreign forces. Not all of these detentions result in prison sentences, but the sheer scale is unprecedented.

In the meantime, Iranian authorities launched a campaign to deport Afghan migrants, who were allegedly actively cooperating with Israeli intelligence. This year, roughly 1.7 million Afghans returned from Iran to Afghanistan, most of them through forced deportation.

Economy and water

According to Iranian political scientist Amir Chahaki, on a day-to-day level there are problems in Iran even more pressing than the executions and repressions: “All these matters are certainly important, but ordinary Iranians don’t pay much attention to them. If you ask an average Iranian, they might not even know how many people are being executed or why.” Instead, Chahaki says, Iranians are gripped by a “sense of fear, uncertainty, and insecurity” — mainly due to the deterioration of the already fragile economy.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Iranians are gripped by a sense of fear, uncertainty, and insecurity due to the worsening economic situation

At first glance, the country’s economic indicators do not seem so bad. In 2020-2024, Iran's nominal GDP grew by 3–5% annually. The unemployment rate is moderate at around 9%. “But people are becoming poorer; everything is being wiped out by high inflation,” Chahaki explains.

Indeed, according to official data, average price growth has been 30–45% annually since 2019. At the same time, economists estimate that real inflation for ordinary citizens may be an order of magnitude higher.

Unemployment figures are also questionable. Official statistics count only those registered as unemployed at the labor office, while most Iranians see no point in filing such a registration. A deeper analysis shows that employment in Iran continues to decline gradually, with women’s employment falling faster than men’s.

This year, another fear has been added to the usual anxieties: an unprecedented drought threatening water shortages. “Previously, Iranians had only heard of water-related protests in southern Iran — in the provinces of Sistan and Baluchestan, or Khuzestan. But now, for the first time, water has been cut off in some districts of Tehran. This creates a great deal of fear,” Chahaki says.

The water crisis in Iran is the result of three factors: an arid climate, global warming, and ineffective water management policies. According to Kaveh Madani, director of the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment, and Health, the situation has already gone beyond a crisis and appears to be a “water bankruptcy.” “For many years, Iran has been spending more water than the country could afford,” Madani explains.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

For many years, Iran has been spending more water than the country can afford

Madani’s own story is illustrative. The administration of reformist President Hassan Rouhani initially sought to attract talented Iranians who had left the country. Madani, a rising star in water management research at the time, seemed a suitable candidate to address Iran’s water problems. In 2017, he became deputy head of Iran’s Department of Environment.

From his first days in that position, Madani pointed out that the country’s main problem is agriculture, which accounts for about 90% of water consumption in Iran. Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Tehran has aimed to build a “resistance economy” that would allow the country to produce all necessary goods domestically, despite the effects of international isolation. One of the key areas of this policy was agriculture — dams were built and wells were drilled with little regard for the larger effect on the country’s water supply. Farmers even received water for free.

These measures produced results, and Iran was generally able to meet most of its food needs. But many of the crops widely grown in the country — such as rice, tea, sugarcane, watermelons, and melons — require large amounts of water. Madani insisted that the country could not afford to continue the same policy and that agriculture needed urgent restructuring, with an emphasis on crops that require less water. Those could be imported.

The problem is that agriculture in Iran is not only the foundation of food security but also an important economic asset, with its own beneficiaries and patrons. Madani’s work quickly led to him being summoned for interrogations by representatives of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, while media controlled by Iranian conservatives published supposed exposés accusing the scientist of working in the interests of foreign powers.

The climax came with the publication of a photo from a private event somewhere outside Iran. It showed Madani in front of wine glasses, a clear violation of the Islamic Republic’s anti-alcohol laws committed by a government official. In 2018, under pressure and following the arrest of other environmentalists in Iran, Madani left his post and the country.

“The water bankruptcy situation was not created overnight. The house was already on fire, and people like myself had warned the government for years that this situation would emerge,” he told Fox News.

New war on the horizon

People’s anxiety is further heightened by the likelihood of a new war with Israel, Chahaki says. “During Israel’s strikes in June, there were no bomb shelters, no warning systems — nothing. People simply hid in underground parking lots or tried to flee Tehran. And now nothing is being done: the authorities are preparing [for a new war], building new missiles but not bomb shelters,” the expert complains.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The authorities are preparing for a new war by building new missiles, but not bomb shelters

These fears are echoed in the West as well. For example, after interviewing officials and analysts from various countries, The New York Times concluded that a new round of Israeli strikes on Iran is almost inevitable. Despite the damage inflicted during the 12-day war, Iran’s nuclear program was not destroyed. Given that Tel Aviv considers Tehran’s nuclear industry a serious threat, its motivation to finish the job remains very high.

Although Iran’s main air defense forces were destroyed during previous strikes, Tehran is seeking to restore its capabilities, with Russia playing an important role in this process. As The National reports, Iran is currently compiling lists of specific types of weaponry it is seeking to import in the near future.

Priority is given to acquiring Su-35 fighter jets and air defense systems, including Russian S-400 and Buk complexes. The main problem is that over the past two years, Russian defense industry capacities have been consumed by increased domestic orders amid the war in Ukraine. As a result, Russian arms exports to the Middle East and North Africa have fallen by 83% compared to 2020.

However, according to the same sources, Tehran is seriously hoping for a swift reconciliation on the Ukrainian front. In that event, Russia’s expanded defense industry would need new arms importers, and the perpetually warring Middle East could become a lucrative market. At the same time, such a scenario only increases the likelihood of new Israeli strikes on Iran, as Tel Aviv would want to take action quickly, before Iran strengthens its defensive capabilities with foreign assistance.

The Iranian volunteer paramilitary organization, one of the five so-called “forces” within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).