Summing up the economic results of the year, many Russian economists say that “everything is not so bad”, referring to the usual indicators, such as GDP of the rates of unemployment, inflation or exchange of the ruble. Judging by these, “GDP has declined less than expected,” unemployment and inflation are virtually nonexistent, and the ruble has “stabilized,” but does this really mean that the country is not in economic crisis? Vladimir Milov explains why these indicators are irrelevant at a time of war, the crisis is already in full swing (even if the average citizen cannot see it yet), and the payback for Putin's military ambitions will be dire for Russians.

The discussion about the results of the year for the Russian economy often begins with the question of why it has survived the war and the sanctions relatively easily. But was it easy? The actual reduction in economic activity, according to various objective indicators, was between 5% and 10%, a very serious drop.

Moreover, there are no prospects for any real growth; Putin has failed to create an alternative military-economic model. All the current methods of stabilization - draconian regulations such as the abolition of the free convertibility of the ruble, import substitution, a turn to Asia, parallel imports, bypassing sanctions through third countries - are only temporary half-measures and cannot create a sustainable economic system. One shouldn't be deceived by what currently seems to be a stabilization.

First of all, a few words about the “smoke and mirrors effect” that accompanies such discussions. If you look at the spring forecasts, most economists never predicted a complete collapse of the economy similar to the collapse of the USSR – but rather the onset of unprecedented economic difficulties. Those difficulties did emerge and are now progressing, there is no hiding from this fact. Furthermore: what economists call a catastrophe (the 5-10% drop in economic activity that few economies around the world have experienced; such a drop usually has far-reaching consequences) is not visible to the average person. People have different criteria - they still have food available in the stores and wages paid regularly; it means that the “collapse” has not happened yet.

However, the economic situation should be judged by an in-depth analysis of the growing trends, rather than by the situation in a store next door, otherwise you may be in for an unpleasant surprise, as in the autumn of 1991 or in August 1998. Back then, the trends were evident to everyone and were discussed by economists in detail, but for many Russians, who were not immersed in economic subtleties, the disappearance of goods from the shelves in 1991 and the default of 1998 came like a complete surprise.

What trends do we observe today?

First. To assess the situation, we should not use a narrow set of macro-indicators, which economic analysts adore and which are either prone to manipulation or meaningless under the current circumstances - some call them “Potemkin indicators”. First and foremost, GDP. In peacetime, GDP - composed of profits, wages and taxes – adds a multiplier to the economy. Profits are invested, wages are used to buy goods and services, taxes are used to pay salaries to public sector employees and to make investments in economic projects. In wartime, GDP includes such factors as the production of arms, ammunition, and equipment for the army, which do not create multipliers for the economy. A tank that has been destroyed, artillery shells that have been expended, and special clothing for the military (for example, this year Russia has been breaking records in the production of special clothing because of the war) - all of it remains on the Ukrainian soil and does not add anything to the economy.

Therefore, saying that “the GDP decline was less than expected” is meaningless. Forget about GDP, it is not a proper indicator today. Economists should think about whether it is currently necessary to take into account the dynamics of Russian GDP in a serious analysis at all.

The same is true for unemployment: although nominally it is record low in the country, if we add hidden unemployment (and according to Rosstat, there are 4.7 million hidden unemployed in the country today (follow this link to see page 229) we get more than 8 million people, or more than 10% of the total workforce. The last time we had this level of unemployment was in 1997-1999. Hidden unemployment comprises part-time employment, downtime or leave without pay. 70% of hidden unemployment is leave without pay, essentially no different from unemployment.

The last time we had this level of unemployment was in 1997-1999

The authorities boast that they have “brought inflation under control”. But the calculation methods raise more and more questions. For example, the moderate decrease in real disposable income announced by Rosstat (a mere 1.5%) does not correspond to a steady decline in retail trade turnover by about 10% since April (without subsequent recovery); it turns out that Russians earned about the same amount as last year but have been making 10% fewer purchases.

Of course, we hear from high tribunes about “the transition of the population to a conservative behavior model”, but we can hardly believe it, especially given the VTsIOM data showing that a third of Russians began to save on food and basic necessities in 2022. Most likely, the explanation is that Rosstat has discounted real income by an underestimated inflation rate, but if we use the actual one, income will drop by about the same 10% as retail sales.

The situation is similar with investment: the authorities have reported an almost 6% growth (!) over the 9 months, although the capital has been flowing out at a record rate since 1994: the Central Bank predicts a $251 billion outflow of capital this year, so how can there be any investment in such an environment? That's right: if you look at the Rosstat data in detail, investment is growing only in sectors that can be associated with the war in one way or another (rail transport, public administration and security, etc. ); the rapid growth of investment in construction dwindled to zero over the first few months of the year, and there has been a decline in such areas as manufacturing, trade, agriculture, telecommunications.

And the notorious “strengthened ruble”. In fact, the ruble exchange rate became the main propaganda indicator for the authorities, designed to demonstrate that “all is well” and “sanctions do not scare us”, both at home and internationally. However, firstly, the artificial strengthening of the ruble has not brought anyone any benefit – it only harmed exporters and the budget, as has been openly acknowledged by the officials. Secondly, it was achieved by draconian measures that in fact destroyed the ruble's free convertibility. Contrary to numerous accolades of the Central Bank's “professionalism” it should be noted that the blow to Russia's free convertibility of the national currency will be remembered for a long time, longer than the 1998 default; after all more than 30 years of currency liberalization have been wasted. Thirdly, there is no international demand for the ruble, and the reduction of oil and gas revenues kills its prospects - since June the ruble has depreciated by a third, from 50 rubles per dollar to more than 70 rubles per dollar, and the process will inevitably continue.

More than 30 years of currency liberalization have been wasted

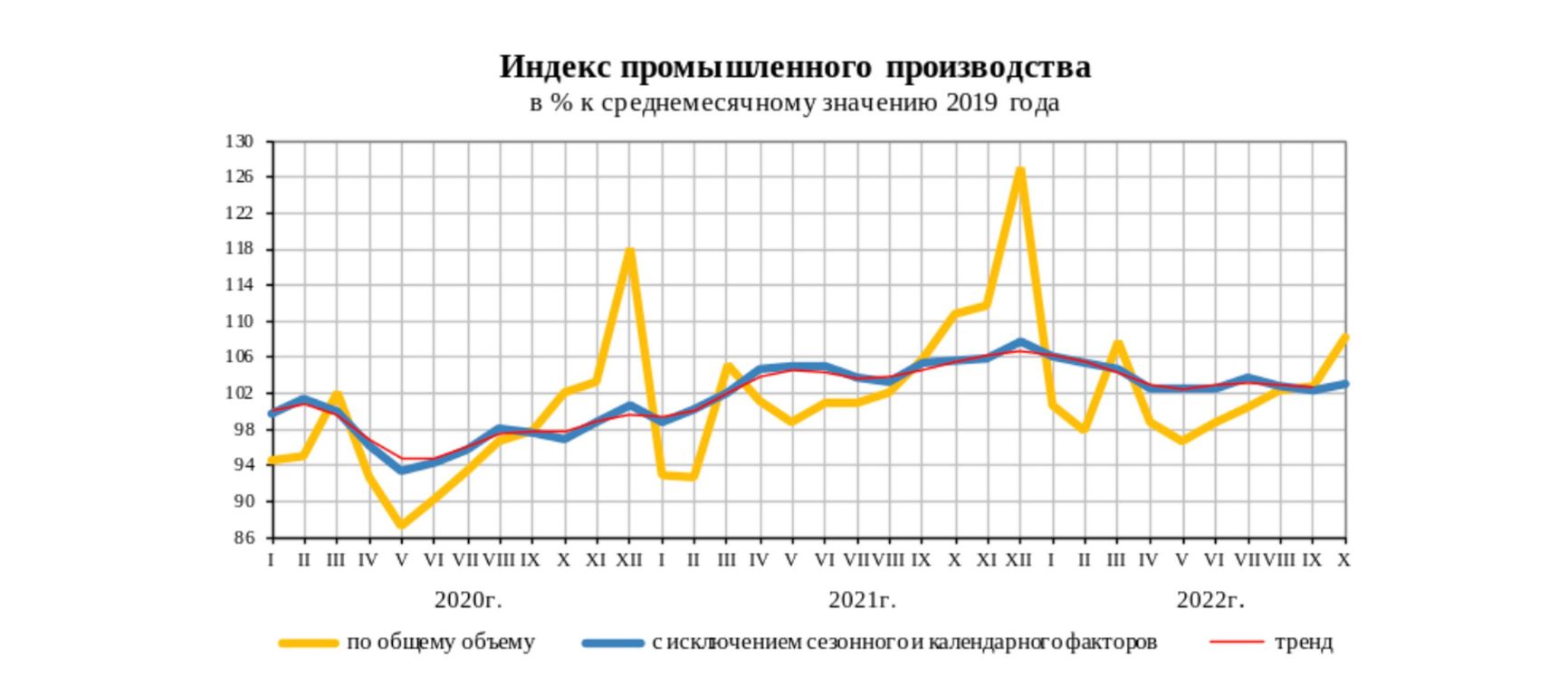

What should we look at, beyond the narrow set of “Potemkin indicators”? For example, Rosstat continues to publish rather detailed statistics on the situation in industry. It shows that the collapse occurred in all industries producing more or less complex products - not only in the automotive industry (a 66% drop in production over 10 months, compared to the 2021 level) but also in transport engineering, engine construction, production of household appliances, etc.

All of these industries, which have fallen due to the absence of access to Western technologies and components, are very job-intensive (complex assembly facilities require a large number of skilled workers), unlike, for example, the food industry, for which import substitution is easier although it does not create a large number of jobs. The automotive industry alone, according to the government's own estimates, creates about 3.5 million jobs directly and in related sectors. But what we observe is that the manufacturing industry is the largest contributor to the above-mentioned latent unemployment: over a million workers are on unpaid leave. In all, more than 25% of manufacturing workers are exposed to various forms of hidden unemployment.

More than a million workers are on unpaid leave

The mineral extraction industry has also begun to collapse: hard coal production is down 7%, while natural gas production is down more than 20%. The reason is the severance of relations with the European energy market; the situation will drastically worsen in 2023 when the European oil embargo enters into force. For example, in a recent interview with RBC, the head of Bank Otkrytiye and former Finance Minister Mikhail Zadornov predicted a decline in oil production from 525 million tons this year to 475 million tons next year. By the way, the interview is worth reading in its entirety, because Zadornov was surprisingly outspoken in describing all the difficulties that the sanctions had been creating for the Russian economy and import substitution – and he did not announce any particularly bright prospects.

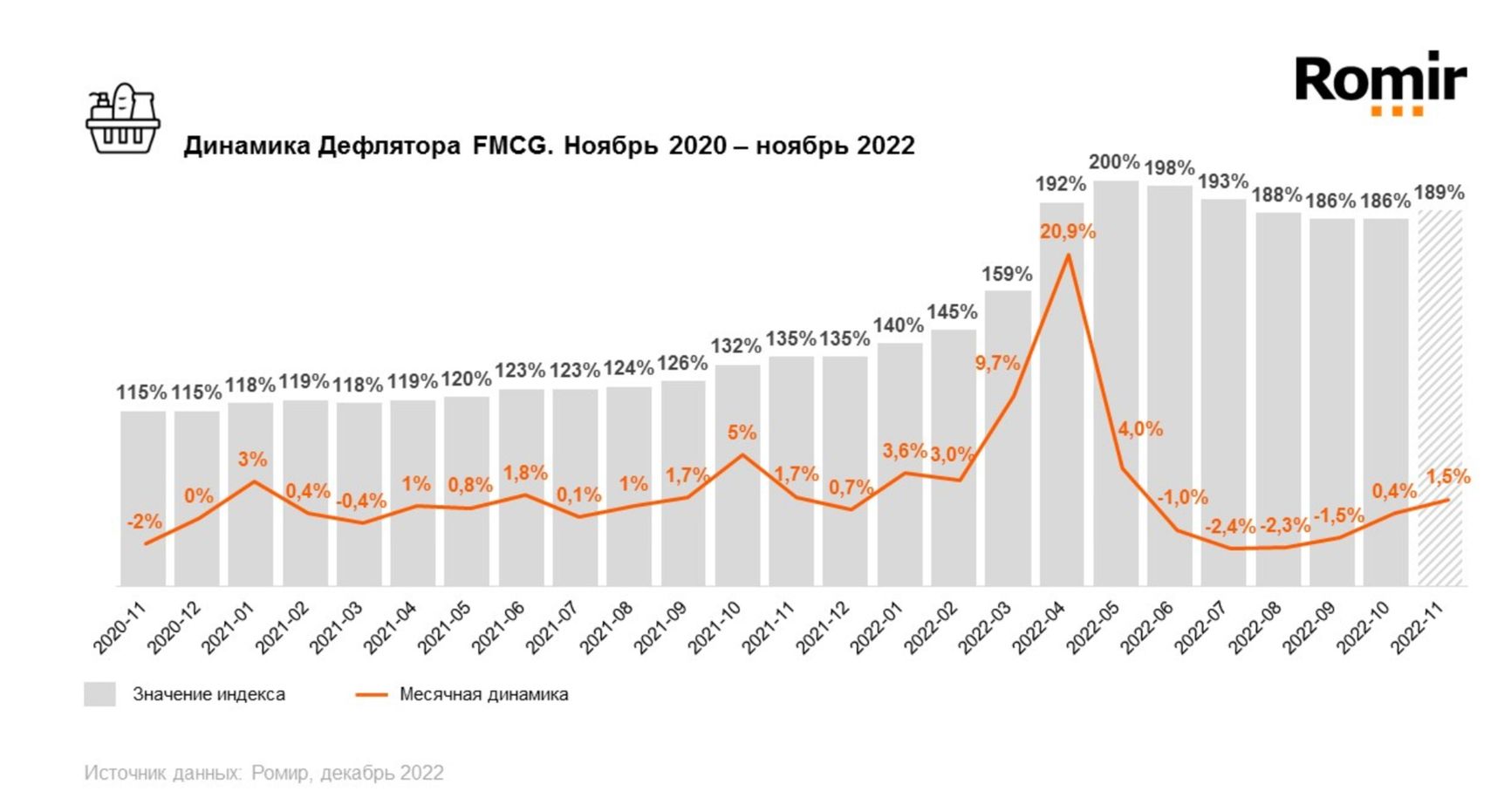

There are deep problems not only on the supply side, but also on the demand side: retail sales have fallen by about 10% year-on-year since spring, and the situation has deteriorated even more since the mobilization started - which even Putin has to admit. Inflation rolled back slightly after the spring peak but has been on the rise again, as evidenced not only by Rosstat data but also, for example, by Romir's monitoring of prices for fast-moving consumer goods.

At the December press conference, Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina listed almost all current trends as pro-inflationary - budget deficit being financed from the National Welfare Fund, mobilization, rising labor market costs, supply chains being reoriented to Asia and higher logistics costs.

The situation with the National Welfare Fund is also not good: there is now only 7.5 trillion rubles worth of so-called “liquid assets” (cash not invested in stocks and bonds of state-owned companies) left there. This year, the Finance Ministry has raised the estimate of the budget deficit to 2% of GDP, or nearly 3 trillion rubles. What lies ahead is the oil embargo and the collapse of budget revenues. Due to the decline in economic activity, non-oil and gas revenues of the federal budget fell by about 5% over 11 months compared to 2021. The National Welfare Fund is likely to be spent at a faster rate, and this method of closing the budget deficit is not much different from money emission, Nabiullina admits. She also notes that at present the state remains the main driver of investment, while private investment is declining. But the exhaustion of budget capabilities means that this process is finite.

The notorious import substitution is not really working - according to the Rosstat data, in the first 10 months of the year the growth in food production was 0.3%, beverages grew by less than 4%, meat, milk and eggs 1-4%, clothing 0.5%, textiles less than 10%. The overall growth in agricultural production occurred only because of the high grain harvest – the situation looks bad with other crops: production is either decreasing (sunflower, sugar beet) or stagnating (potatoes, vegetables). However, the beauty of grain harvest will not last long - farmers complain about declining profitability of grain production due to export restrictions and controlled domestic prices, and in spite of the government's requests they have already been reducing the sowing of wheat and rye.

Against this background, the establishment's early triumphant rhetoric about Russia “coping with the sanctions better than expected” is being replaced by more gloomy talk about the fact that we've somehow lived through the year 2022, but it is unclear what will happen next. Zadornov and Nabiullina have been discussing it, but the toughest formulation of this can probably be found in the interview Mikhail Sukhov, director of the AKRA rating agency, gave to RBC: “The timeframe for the economy to reach the pre-pandemic level is beyond the scope of five-year forecasts. I don't think the picture is rosy in any way.”

“The timeframe for the economy to reach pre-pandemic levels is beyond the scope of five-year forecasts”

The picture is not rosy indeed. Beyond the five-year forecasts means nowhere near. Whatever predicting skills Russian officials may possess, they still don't see any growth on the horizon. The main takeaway of the year: having somehow coped with the first blow, the Russian economy looked around and realized there are no good prospects. For Russians this means one thing: they will continue to become poorer, and their quality of life will deteriorate. Forget about new foreign-made cars or the usual quality of cellular communication or the Internet, or many other customary benefits of civilization.

In general, before the war, calculations of the dynamics of Russians' real incomes showed that since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 citizens have grown poorer by 10-15% in real terms. Taking into account the actual (rather than Rosstat's) assessment of the real purchasing power of Russians (based on the collapse in retail sales), by the end of 2022 the population ended up 20-25% poorer than it was in 2013. And there are no prospects for improving the situation (“beyond the scope of five-year forecasts”).

That's the price of Putin's imperialism and geopolitical adventurism.