At the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum that wrapped up in mid-May, Russia’s Ministry of Justice advocated for the immediate criminal prosecution of so-called “foreign agents” — while simultaneously proposing immunity for those who commit crimes “in defense of moral values.” This contradiction highlights the ever-expanding space for repression in Russia, which has seen a sharp rise in politically motivated criminal cases since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Not only activists with visible civic positions are being targeted, but also those who have not expressed explicit opposition to the war. Even those who remained silent are now being crushed by the system, notes Olga Romanova, a journalist and the founder of the prisoners' rights organization Russia Behind Bars. Although open protest leads almost inevitably to prison, Romanova believes there are still ways to quietly sabotage the authorities.

A typology of repression

Criminal prosecutions on political grounds in today’s Russia look a lot like the newly restored Stalin bas-relief at Moscow’s Taganskaya metro station: almost identical to the original, but made of cheap plastic instead of porcelain. And yet, many in Russia seem to approve — even if the more “ideologically refined” types grumble that it’s shoddy work, and that it ought to be done properly.

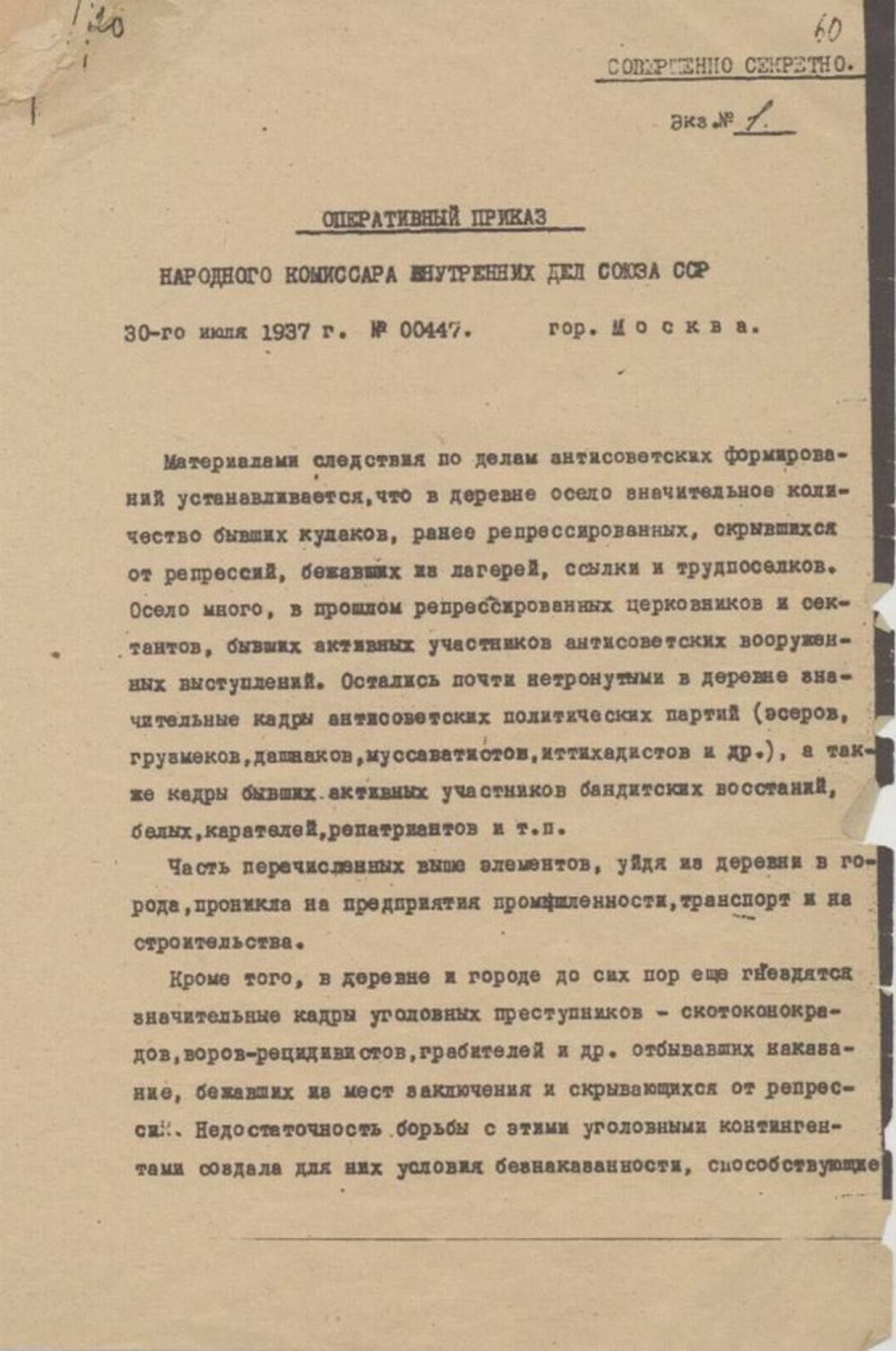

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

Russians take selfies and lay flowers at the feet of the newly-restored sculpture of Stalin at Moscow’s Taganskaya metro station.

It has become commonplace to assert that today’s repressions cannot be compared to those of the 1930s. Security officials, especially the more shrewd among them, often remark that “investigation is a creative process.” And the FSB has become the chief “artist.” The agency holds a monopoly on political repression, and even when it appears that a case is being handled by the Investigative Committee or, God forbid, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), it is still the FSB calling the shots.

The era of independent operations by the MVD ended at the same time the careers of General Denis Sugrobov and Colonel Dmitry Zakharchenko did — way back in the mid-2010s. The Investigative Committee no longer acts on its own initiative either, especially after the July 2016 arrests of top figures in its own internal security division (see: the cases of Mikhail Maksimenko, Alexander Lamonov, and Denis Nikandrov).

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

The Kremlin has granted the FSB a monopoly on political repression.

Of course, the FSB has no interest in ordinary crimes like robbery, rape, domestic murder, theft, or drug dealing. But when suspects, defendants, or convicts from these categories are sent to the front, their deployment must be cleared with the FSB — and in some cases, permission is denied. This primarily applies to officials and former security personnel — Dmitry Zakharchenko, for instance, was not allowed to join the so-called “special military operation,” clearly because there are still unofficial issues surrounding his case. The reason is simple: for the wealthy and well-connected, such wartime recruitment would effectively serve as a form of amnesty, since their service would likely be done in units stationed comfortably in the rear.

In fact, this informal power to “pardon” might be the only innovation in today’s repressive system. Everything else consists of poorly forgotten old practices. The FSB hasn’t invented anything new — all of its tactics are drawn from the Stalinist 1930s.

Together with legal expert Andrei Tarasov, we propose the following typology of repression — not based on legal codes or the specific criminal charges (which may be non-political or war-related), but on the underlying motivations behind the cases.

1. Repression centered on individuals and organizations

In the 1930s, the targets were Leon Trotsky, the “Industrial Party,” Nikolai Bukharin, the Russian Orthodox Church, and virtually all religious denominations. Today, they include gallery owner Marat Guelman, the late Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (ACF), election monitoring organization Golos, the independent publication Meduza, human rights NGO Memorial, and even the Jehovah’s Witnesses — with authorities methodically “dismantling” their objects of interest.

Let’s examine three examples from among hundreds of similar cases:

- Journalist Tatyana Felgengauer has been subjected to a sustained smear campaign. She faces multiple criminal charges, has been arrested in absentia as a “foreign agent” for failing to meet legal requirements associated with the designation, and is the subject of a new case for allegedly “justifying terrorism.”

- Election monitoring expert Grigory Melkonyants is a prime example of a target whose case was built around both the individual and the organization — in this instance, Golos — despite the absence of any formal legal logic. Melkonyants was recently sentenced to five years in prison for “organizing the activities of a foreign or international NGO declared undesirable in Russia.”

- At least 60 people have been prosecuted in a massive campaign targeting the Anti-Corruption Foundation. Among those drawing the authorities’ ire are allies of the late Alexei Navalny, journalists, and even small-time donors. In 2024, 21 people were arrested and 26 fined for “using symbols” associated with the ACF or Navalny. Similar fines are still being issued in 2025.

2. Serial repression

In the 1930s–1940s, the accusations levied against dissidents included: anti-Soviet agitation, slander of Soviet authorities, glorification of bourgeois lifestyles, anarchism, and terrorism (both as an act and as a political charge).

Today’s equivalents are: LGBT “propaganda,” discrediting the military, spreading “false information” (or “fake news”) about the Russian Armed Forces, justifying terrorism, terrorism itself, the incitement of hatred, and rehabilitation of Nazism.

Among the examples are:

- Anna Ganina, a nurse from Yekaterinburg, who was convicted for a single anti-war comment on the Odnoklassniki social network — a textbook case of how Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code is used as a serial tool of intimidation.

- Vladimir Rumyantsev, a radio enthusiast from Vologda, who was convicted for reposting anti-war content — even though he was not the author.

- The “Guelman case,” which involves searches, interrogations, and pressure on the “anti-state” art community as a whole.

We have yet to see hard proof, but it would be fascinating to learn whether regional authorities are receiving secret instructions similar to NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, which established quotas for repression: for example, 5,000 people to be executed in Moscow Region (Category I), and 10,000 to be sent to the Gulag (Category II). That order remained classified until the 1990s. Someday, we may see today’s modern “execution lists,” too.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

NKVD Order No. 00447

Treason has emerged as its own “serial” category of prosecution — classic Stalinist territory. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine in February 2022, the number of convictions for treason has increased nearly tenfold. A total of 792 people have been charged with treason-related crimes since the war began, with 359 convicted in 2024 alone.

Even minor financial aid to Ukraine — or merely sending a text message like “I’m driving and surrounded by a convoy of tanks,” or sharing information about troop movements, or attempting to contact foreign nationals, or taking part in anti-war protests, or simply posting anti-war content — can serve as grounds for prosecution. These cases are increasingly the result of entrapment — online conversations in which FSB agents pose as Ukrainians or anti-war Russians, coaxing targets into engaging in incriminating discussions.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

A total of 792 people have been charged with treason-related crimes since the war began, with 359 convicted in 2024 alone.

Treason stands out because it refers not only to a single article of the criminal code, but to an entire group of crimes, including espionage. On Jan. 1, 2023, a new charge came into effect: Article 275.1 of the Russian Criminal Code, covering “confidential cooperation with a foreign state or international organization.” The first person convicted under the new law was journalist Nika Novak from the far-eastern Chita Region. Novak received four years in prison for allegedly providing foreign entities with materials that “discredited” the Russian government and its armed forces.

Investigators claimed her actions were intended to destabilize Russia’s domestic political climate during the “special military operation.” Though the case remains classified, it appears the allegations stem from her publications for Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. A change in Novak’s political views prior to her arrest did not help her case.

The group of “traitors and spies” is rapidly expanding. It is no longer limited to journalists and academics (some of whom were historically accused of “selling secrets to China”). Instead, it now includes taxi drivers, couriers, retail workers, students — virtually anyone.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

The sentence handed down to 32-year-old Nika Novak was the first issued against a journalist under the charge of “confidential cooperation with a foreign state or international organization.”

3. At-risk groups

Certain demographics remain particularly vulnerable: politically active teenagers, ethnic Ukrainians, Crimean Tatars, Bashkirs, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. These groups were also targeted in the 1930s. Back then, the repressed included “kulaks,” “former people,” and ethnic minorities such as Germans (especially in the 1940s).

The FSB has reported that it foiled an alleged plot to attack police officers in Russia’s Stavropol region on May 9 — Victory Day — claiming the scheme was orchestrated by a group of minors. Nine local residents were detained, eight of whom are teenagers. According to investigators, a resident of the Andropovsky District allegedly joined an “international terrorist organization” via Telegram and recruited eight more individuals from the area, seven of them minors. However, the incident appears to have been a classic case of entrapment.

Another example comes from Nizhny Novgorod. This past April, two local teenagers were each sentenced to two and a half years in prison after their school principal reported them for watching and sharing a video featuring portraits of Hitler and Putin — which had a total of 26 views.

Another high-risk category includes Ukrainians. In April 2025 alone, 27 Ukrainian-born individuals were added to Russia’s list of terrorists and extremists. Since early 2024, the number of new “terrorists” has doubled, driven largely by additions of Ukrainians.

The underlying logic of the system appears to be: “If there’s a person, a charge can be found.” Individuals deemed “inherently hostile” inevitably face repression, while actions against lower priority figures depend on the technical capacity and intimidation needs of the system. Among the most common targets today are everyday people — those who post or comment online.

Several other features of this expanding repressive apparatus are also worth noting.

Mounting a campaign

Before categories 1, 2, or 3 are officially “formed,” authorities often roll out a high-profile test case — usually chosen at random. These are usually accompanied by several attempts at “clarifying” and intimidating the public. One example is the widely known case of pediatrician Nadezhda Buyanova — a harsh, senseless, and evidence-free prosecution that followed from the case against Moscow resident Yuri Kokhovets.

In 2022, Kokhovets made an anti-war comment during a street interview conducted by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. That single statement became grounds for opening a criminal case against him, and in April 2024, Moscow’s Ostankino District Court found him guilty of spreading “fake news” about the Russian army. He was initially sentenced to five years of compulsory labor, but an appeal by the prosecution led the Moscow City Court to impose a harsher penalty: five years in a general-regime prison colony. Kokhovets, who had not expected a harsher sentence and arrived at the hearing without his personal belongings, was taken into custody on the spot. The original “lenient” ruling against Kokhovets had evidently been insufficiently intimidating — hence the need for a new example: the prosecution of Nadezhda Buyanova.

The exact same approach is being used in the new major “book publishers’ case,” which has seen ten people detained. It marks the second attempt to “educate” the public about the supposed dangers of involvement with the “international LGBT movement.”

The first attempt came in November 2024, when small business owner Andrei Kotov, the director of a Moscow travel firm called Men Travel (a name that likely played a role in the charges), was arrested for “organizing and participating in the activities of an extremist organization” — namely, the non-existent “international LGBT movement.” Kotov is believed to have been driven to suicide in pre-trial detention; the authorities seem to have planned a show trial, by all appearances, they took things too far. Since then, ten people connected with the book publishing industry have been arrested on similar charges, and the attention their cases have received all but ensure that the title of the banned book Summer in a Pioneer Tie will linger in the public memory for a long time.

In Stalin’s day, passivity, lack of Bolshevik zeal, sympathy for enemies, concealment of one's class origin, or being a “hidden ‘former person’” put a person at risk, even if they did not take any actions that directly threatened the state. Today as well, the underlying cause of repression is often found not in action, but in inaction. Influential bloggers who failed to make even symbolic gestures of support for the war — those who didn’t “throw a Z salute” — were the first to be targeted. The criminal charges brought so far may not explicitly mention politics, but the coded message is clear: you’re being punished for not showing enough loyalty to the system. This points to an emerging category of criminal offenses — for one’s silence, for “failing to show support,” or for crying insincerely. Some of these charges are already being introduced under economic or domestic pretexts.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

The foundations for repression lie not in action, but in inaction and insufficient loyalty.

Video bloggers and stand-up comedians who have not publicly expressed support for Russia’s “special military operation” often find themselves under financial audit, they are denied distribution licenses, or else they are placed under “preventive monitoring.” In effect, they are facing criminal charges for keeping silent.

What to do if you’re neither a politician nor an opposition activist

Activities that can attract scrutiny include not only posting on social media, but also commenting, reposting, and liking — especially if it is done on platforms that are blocked in Russia. Making donations to organizations labeled as “foreign agents” or “extremist,” taking part in any protest (even small local ones), working or interning at “unapproved” organizations, or maintaining ties with politically targeted individuals also put ordinary Russian at risk of persecution.

Some actions appear relatively safe (based on my personal observations, at least). The passive reading of banned websites via VPN is unlikely, all by itself, to lead to a criminal case — but phone checks at borders or during home searches may lead to deeper investigations. So far, there have been no known cases of persecution for writing letters to political prisoners. Some Russians quietly resist by refusing to denounce their acquaintances, by not spreading propaganda, or by not working with or for the government.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

So far, there have been no known cases of persecution for writing letters to political prisoners.

This passive stance can be ethically fraught — especially for educated professionals. Should a pediatrician treat the child of a judge who jailed a colleague? Should a contractor renovate the home of a prison official known for torturing inmates? Should a copywriter accept a commission from the Investigative Committee? What to do if these government workers are friends?

Forms of everyday resistance according to anthropologist James Scott (“Weapons of the Weak”)

In authoritarian regimes where open protest is impossible, quiet resistance comes to the fore. It is not expressed in slogans and manifestos, but it erodes power from within. In villages, this took the form of imitation of work, silent irony, delays in handing over crops, and pseudo-obedience. Today, it means going through the motions without enthusiasm, refusing to take initiative, or quietly opting out. These actions are invisible, but they are the only form of moral choice available in a situation where everything else leads to criminal prosecution. According to James Scott’s logic, resistance is not an act, but a way of life.

In places like Putin’s present day Russia, offenses that would be condemned in peaceful societies — tax evasion, not completing one’s obligated tasks, everyday disobedience — become forms of silent resistance. No longer just greed, carelessness, or negligence, these actions signal something else. Not yet open protest — but, at least, a refusal to participate in larger crimes.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued on July 30, 1937, was a top-secret directive signed by Nikolai Yezhov, head of the Soviet NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs), and approved by the Politburo. It marked the beginning of the largest mass repressive operation of Stalin’s Great Terror, targeting so-called “anti-Soviet elements” across the USSR.

A kulak (Russian: кулак, meaning “fist”) was a relatively affluent peasant in the Soviet Union who became a target during Stalin’s campaign of forced collectivization in the 1930s.

From 1929 to 1933, Stalin launched “dekulakization” — a violent campaign to “eliminate the kulaks as a class.” Labeled as “class enemies,” kulaks were subjected to mass repression — including expropriation of their land and property, deportation to Siberia, internment in the Gulag, and execution — as part of the Soviet government's effort to eliminate private farming and consolidate agriculture under state control.

The term later became a catch-all accusation used to justify persecution of any rural resistance — regardless of one's actual wealth or status.

In the Soviet Union, “former people” (бывшие люди) was a term used to describe individuals who belonged to the pre-revolutionary elite — such as nobility, aristocrats, tsarist officials, clergy, officers, and members of the bourgeoisie — who lost their status after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“Former people” were stripped of their civil rights, barred from voting, holding public office, or joining the Communist Party. They were monitored by the secret police, often denied jobs, housing, and education — and heir “class origin” was recorded in personal files and could harm their children’s and grandchildren’s life prospects in the USSR.

Many were arrested, exiled, or executed — especially during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.