Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the global arms race has accelerated, becoming a significant burden on the budgets of many countries. However, for Russia itself, a dependence on military spending could prove particularly devastating, writes Oleg Itskhoki, a professor of economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. While military spending worldwide is increasing from around 2% up to 3% of GDP, in Russia the figure has already reached nearly 9% of GDP and 40% of the state budget. Even if the war were to end tomorrow, Russia would find it challenging to rebalance its economy.

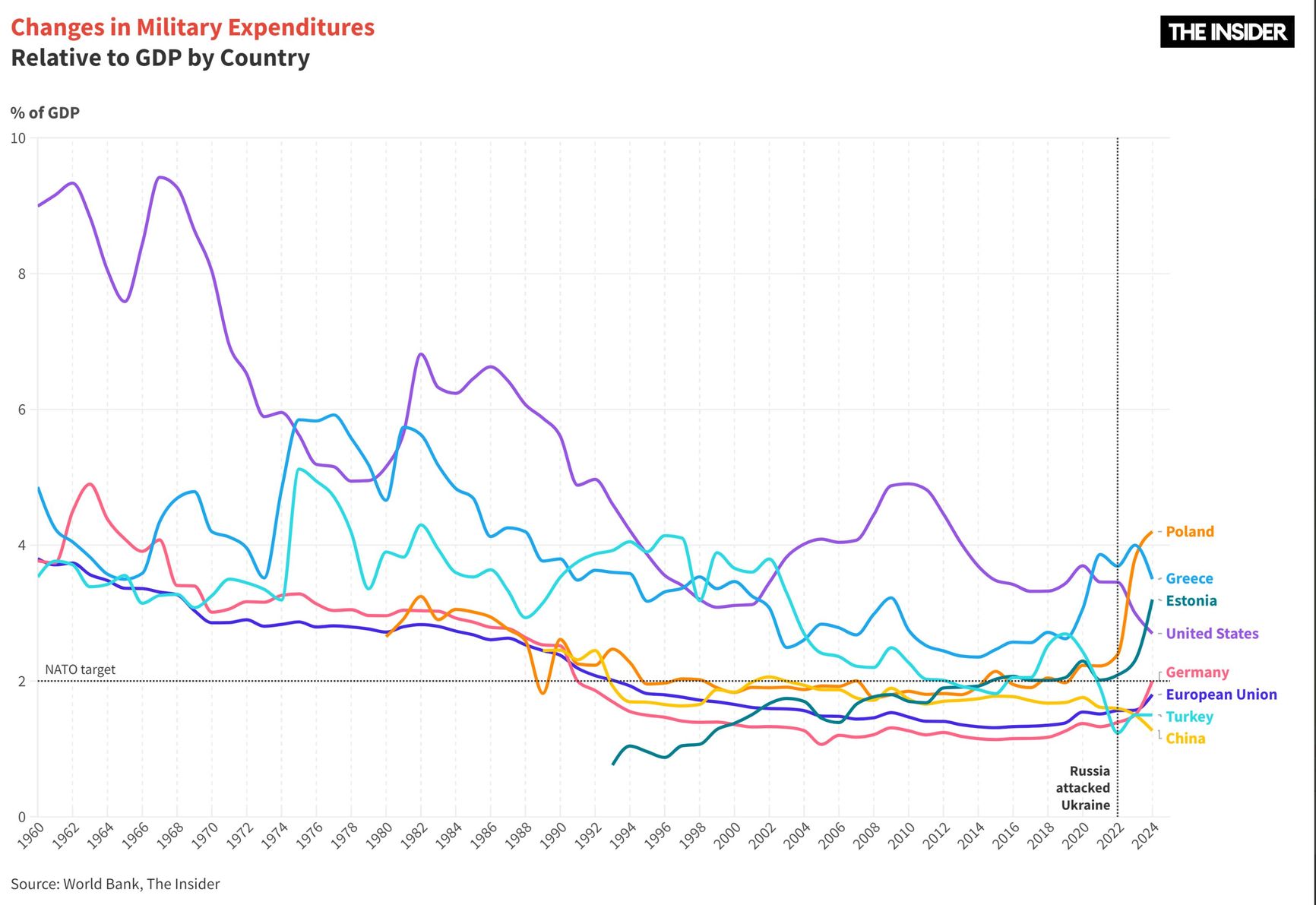

Military spending presents an ongoing dilemma for political leaders. On one hand, it is necessary and must be maintained at a sufficiently high level to deter armed conflicts. For instance, the relatively high defense spending of Poland (4.1% of GDP) and the Baltic countries (2.85-3.43%) makes the escalation of conflict beyond Ukraine less likely. Germany's relatively lower defense spending (2.12%) is still substantial given the size of the country’s economy, which allows Berlin to transfer surplus weapons to strategic partners when the need arises. However, both political considerations and material constraints caused delays in providing arms supplies to Ukraine in the early weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. While fears of “escalation” abounded, at the time there was also a relative shortage of weapons in Western warehouses — the result of low military spending in previous decades.

On the other hand, if war does not occur, military spending is seen as wasteful, diverting resources from productive activities that could improve the population's well-being, as the post-Cold War “peace dividend” surely did. Still, the decision Europe made thirty years ago to significantly cut defense spending and military production appears to have been made in error.

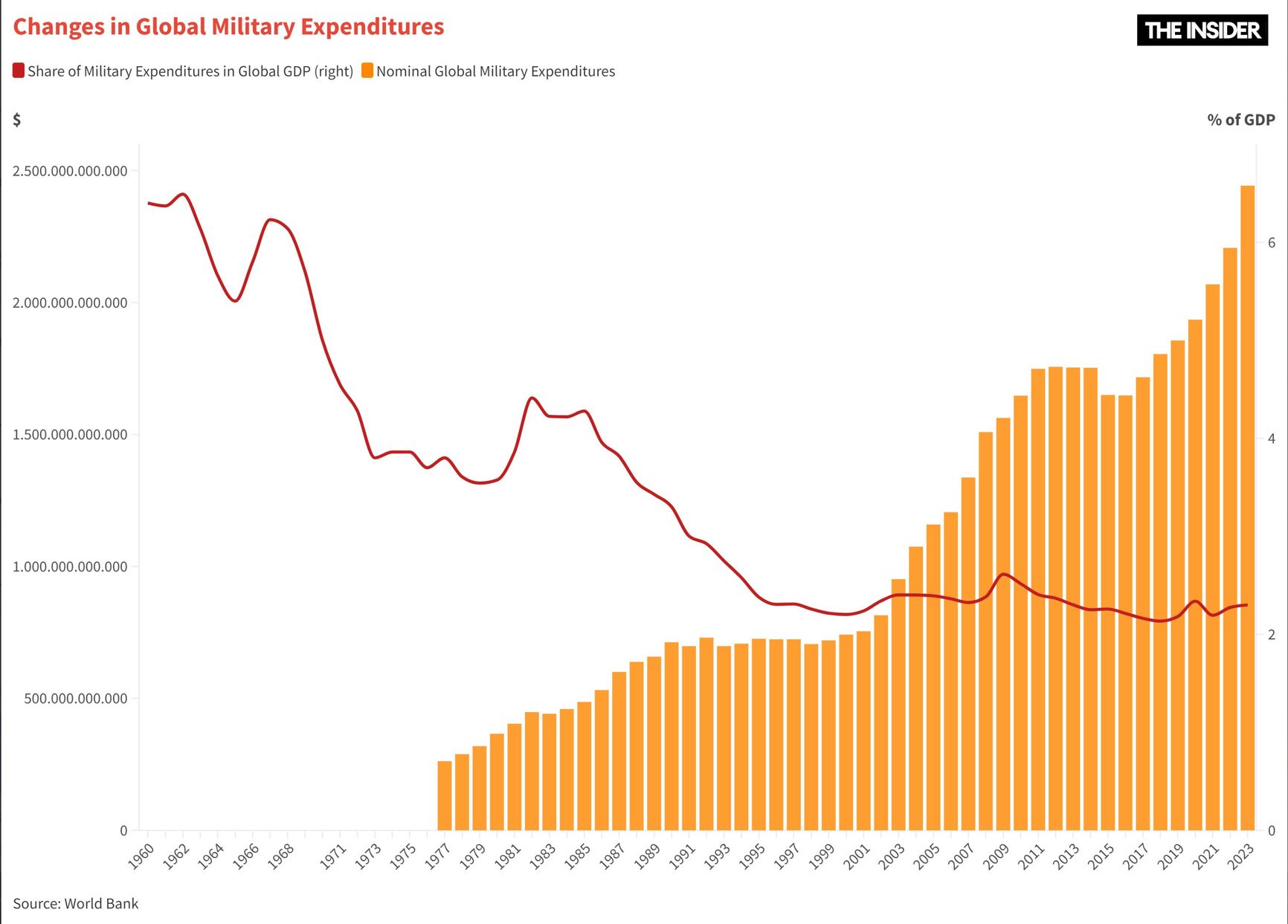

Total global military spending in absolute terms has been growing for many decades. During the Cold War, it amounted to hundreds of billions of dollars and now exceeds two trillion. However, these figures largely reflect economic growth and rising price levels. In percentage terms, spending has actually been declining: while at the height of the Cold War, the share of military spending in global GDP reached 6.5%, in 2023 it was only 2.3% — this despite the fact that defense spending worldwide is growing at a record pace following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Military expenditures are discretionary budget expenses that are approved each year. They constitute more than half of all discretionary spending. However, this is significantly less than the $7 trillion allocated in total to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, it is a fundamental category of expenditure that is unlikely to be reduced, even if the authorities return to the task of reducing public debt and implementing austerity measures.

The United States: balancing economy and international security

Even before it began sending substantial weapons shipments to Ukraine, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq meant U.S. defense spending remained relatively high. However, as America is no longer directly involved in any war, spending has naturally decreased. Following George W. Bush’s 2003 decision to invade Iraq, three successive presidents have sought to minimize America's involvement in international conflicts. Barack Obama avoided direct participation in the Syrian conflict, Donald Trump proclaimed an “America First” principle aimed at avoiding the costs associated with foreign intervention, and Joe Biden withdrew the troops from Afghanistan.

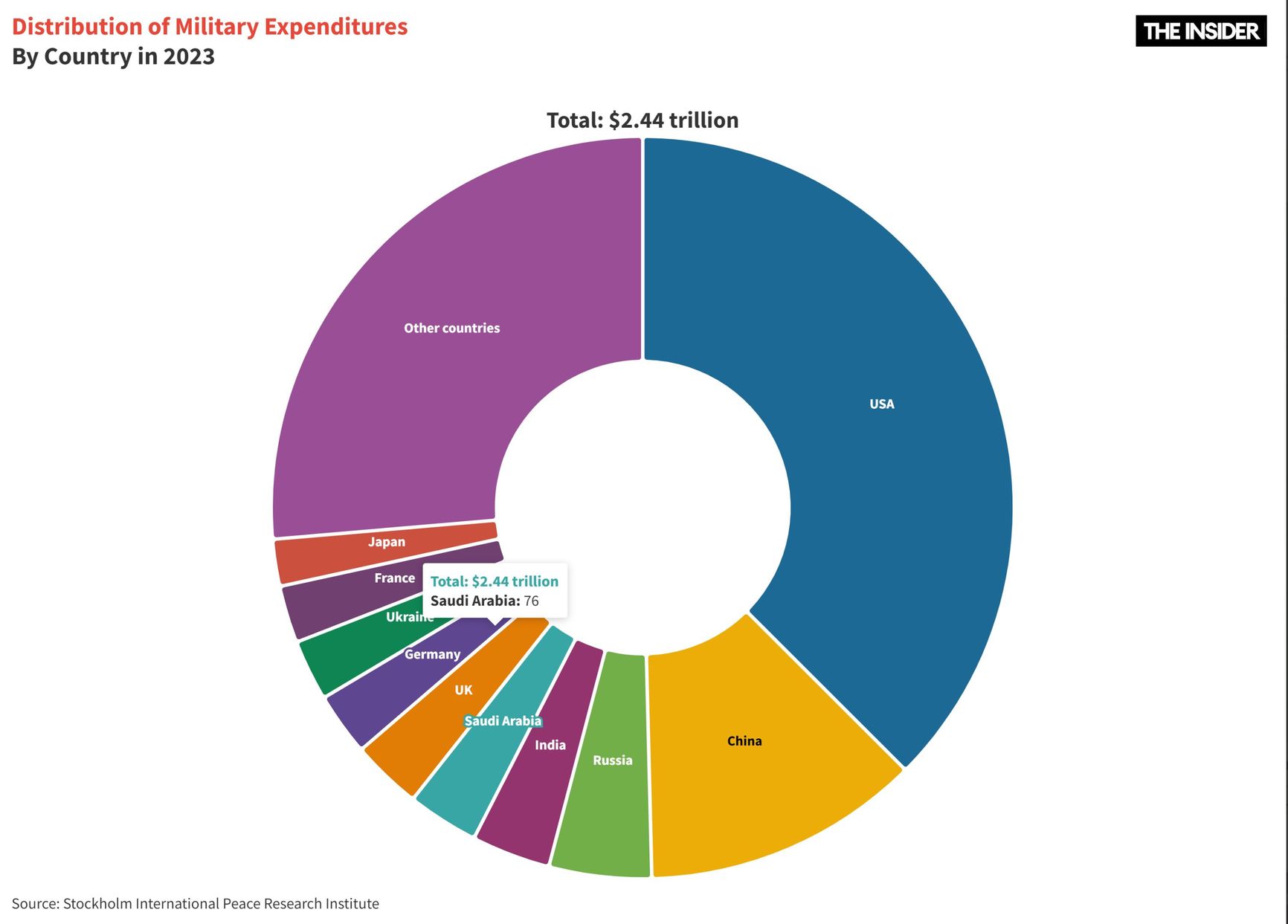

Washington’s cycle of wars and high spending has ended. Military outlays decreased from almost 5% of US GDP in 2010 to 2.7% today. Nevertheless, in absolute figures, this still represents a colossal sum: $884 billion in 2024, accounting for around 70% of NATO countries' spending and almost 40% of global military expenditure.

Military expenditures are discretionary budget expenses that are approved each year. They constitute more than half of all discretionary spending. However, this is significantly less than the $7 trillion allocated in total to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, it is a fundamental category of expenditure that is unlikely to be reduced, even if the authorities return to the task of reducing public debt and implementing austerity measures.

This raises a question: Could America's reluctance to engage in external conflicts and its rejection of the role of global policeman have contributed to the destabilization of the global balance? Is it possible that when America ceases to participate in regulating international conflicts, the outcome is worse than when it intervenes? Perhaps Putin's invasion of Ukraine is a response to the downward trend in U.S. military spending, to Obama's inaction in Syria, and to Biden's withdrawal from Afghanistan? While not a widely popular view, it nevertheless seems to fit the facts we’re all observing.

Currently, US defense spending[1] is increasing again. The government is bringing shuttered factories back online in order to boost production of 155mm artillery shells from 14,400 to 100,000 per month. However, due to its large public debt, the U.S. is unlikely to dramatically increase military spending.. Most likely, defense spending will remain at around 3% of GDP (compared to the current 2.7%), and its relatively minor fluctuations will not significantly impact the U.S. economy.

EU and government defense contracts

In Europe, defense spending has risen sharply in recent years, even if it remains lower than it was at the inception of the European Union. The situation varies by country. In Germany, the share of military spending has been steadily growing since 2015 and is projected to exceed 2% of GDP in 2024. In Poland, it already exceeded the 2% NATO benchmark in 2022 and is expected to surpass 4% of the country's GDP. Defense spending is also slated to exceed 3% of GDP in Estonia, while Greece has long since crossed this threshold, possibly due to the longstanding Greek-Turkish conflict in Cyprus.

An increase in defense spending from 2% to 3% of GDP is generally manageable for EU economies. In fact, state defense orders may offer a sort of Keynesian stimulus, boosting overall GDP in a way that does not seriously detract from production in other sectors. While these unproductive expenditures themselves will not directly enhance the well-being of the citizenry as a whole, they will generate income that can be spent on other civilian goods. This could provide an initial impetus to European economies that have been stagnating in recent years. It is likely not a coincidence that Poland, the EU's leader in military spending as a share of GDP, is also among the leaders in economic growth, nearly reaching the levels of major Western European countries despite emerging from the Soviet-dominated Eastern bloc just over three decades ago.

Military expenditures are discretionary budget expenses that are approved each year. They constitute more than half of all discretionary spending. However, this is significantly less than the $7 trillion allocated in total to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, it is a fundamental category of expenditure that is unlikely to be reduced, even if the authorities return to the task of reducing public debt and implementing austerity measures.

Increased defense spending is also observed in the Asia-Pacific region and Africa. China ranks second globally in military spending, and its defense budget continues to grow. Taiwan is compelled to follow suit, although its investments are not comparable to China's: about $17 billion versus almost $300 billion. However, these increases do not yet represent such a large share of world GDP that their reduction, in the event of a new “détente” and stabilization, would cause a significant shock. Such an impact can only be predicted for individual countries whose economies are becoming militarized, and here, Russia is the prime example.

Russia and the defense spending addiction

In Russia, spending on defense and security will amount to 8.7% of GDP this year, a figure on a vastly different scale from the 3-4% upper limit on display in Western countries. Russia’s military expenditures account for almost 40% of federal budget, totaling 14.2 trillion rubles (more than $150 billion). This figure is only slightly smaller than the size of Ukraine's entire pre-war economy — an annual GDP of around $200 billion.

On paper, the Russian economy is currently growing, and the statistical success is largely the result of the stimulus provided by large government expenditures on the war. Up to a third of this growth is driven by the military-industrial complex and related industries. But what will happen when the war stops? It's likely that, even if there is no direct necessity for continuing to produce drones and artillery shells, Russia will nevertheless maintain a high level of military spending.

This is not due to any sort of Kremlin logic about the need to maintain a perpetual conflict with the Western world. Instead, it is simple economic reasoning: abruptly cutting off the injection of more than 8% of GDP in government spending is impossible without causing a severe economic collapse. For comparison, during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, spending and GDP in most countries decreased by “only” 1-2%.

That’s precisely why high military spending will probably remain an integral part of Russian economic policy until the budget and the National Welfare Fund of the Russian Federation are depleted. The reduction of military spending will likely become a forced emergency measure brought about by a budget crisis. Until that day inevitably comes though, the Russian economy will almost certainly continue pouring unconscionable amounts of its industrial and human capital into the production of death and destruction.

Military expenditures are discretionary budget expenses that are approved each year. They constitute more than half of all discretionary spending. However, this is significantly less than the $7 trillion allocated in total to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, it is a fundamental category of expenditure that is unlikely to be reduced, even if the authorities return to the task of reducing public debt and implementing austerity measures.