On Aug. 4, Russia announced that it would no longer adhere to a self-imposed “moratorium” on the deployment of missiles previously banned under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which has been defunct since the U.S. withdrew in 2019 over alleged Russian violations. The INF Treaty, originally signed in 1987 between the United States and Soviet Union, forbade both countries from possessing ground-launched ballistic and cruise missile systems with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. Now, as Moscow openly resumes its development of such missiles, European members of NATO must respond by ensuring that their own arsenals are sufficiently robust to guarantee peace on the continent.

Russia was never in a position to credibly issue any sort of moratorium regarding missiles previously outlawed under the INF Treaty. A technical analysis of the range of Russia’s 9M729 cruise missile — the system the led to America’s withdrawal from the INF — strongly indicate that the missile exceeds the proscribed range limits by a significant margin. This fact brings with it serious implications for the future of European security, particularly regarding the potential for a missile arms race.

History of non-compliance

The key issue surrounding the INF Treaty centers on the 9M729 (NATO designation SSC-8) ground-launched land-attack cruise missile. Russia claims the 9M729 has a range of less than 500 kilometers and that it was therefore INF-compliant. The United States and its NATO allies have rejected this assertion.

The Iskander-K missile complex

Photo: mil.ru

The United States first publicly raised concerns about the missile in 2013. In total, American officials engaged their Russian counterparts on the 9M729 issue more than 30 times before deciding to withdraw from the treaty after Russia proved unable and unwilling to address Washington’s concerns.

U.S. assessments of Russian noncompliance rest on two main points. First, the United States claims to have tracked test launches of the 9M729 from both fixed and mobile launchers. These demonstrated missile trajectories above and below 500 kilometers.

The specific collection methods and launch site locations have not been publicly disclosed, but U.S. statements indicate that satellite imagery, telemetry (interception and analysis of the missile’s in-flight data transmissions), and other intelligence sources were involved.

Second, U.S. assessments are probably also based on a technical assessment of the missile’s characteristics — notably its maximum range in standard trajectories.

Relying on unclassified data alone, it is impossible to verify U.S. claims that it collected testing data proving Russian noncompliance with the INF Treaty. However, we do have reasonably good technical information on the missile and its components, which allows for an independent assessment of the technical side of the issue. It is unclear how much weight the United States placed on such technical evaluations in its engagements with Russia — given that the American side could share classified test launch data directly with its Russian counterparts, non-public information likely played the greater role.

The anatomy of a rocket

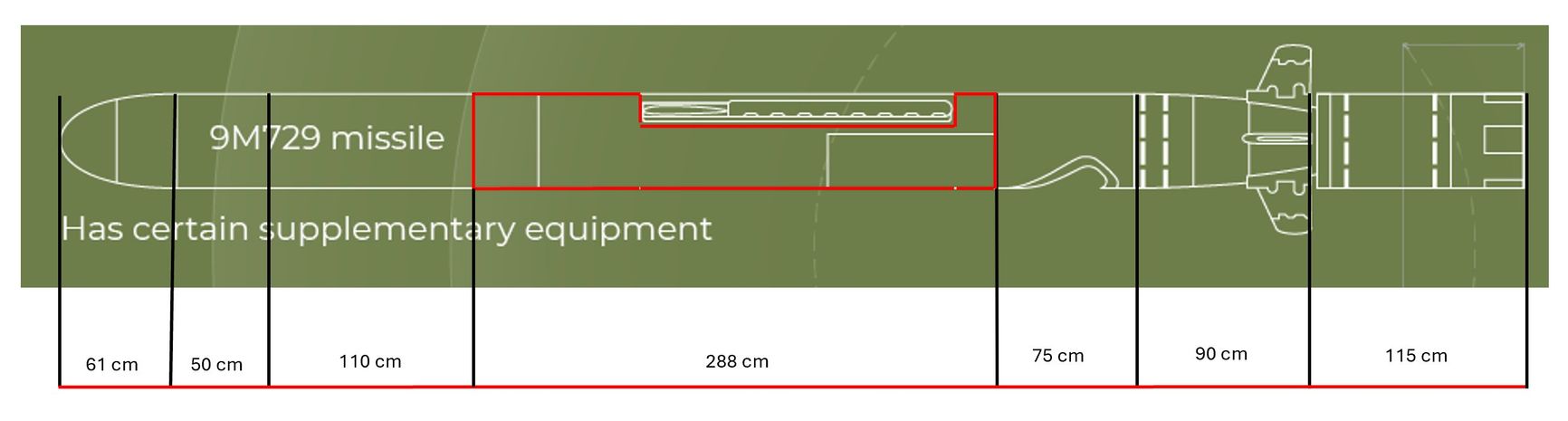

From a technical perspective, the key factor is the overall length of the 9M729, as this ultimately determines the size of the internal fuel tanks, which in turn largely define the missile’s range. Unfortunately, the overall length of the 9M729 is not known. However, we can estimate it with some accuracy. As other analysts have pointed out, the 9M728 (the lower-range “friendly” cousin of the 9M729) and the 9M729 appear to be based on the Kalibr family of missiles. Notably, the 9M728 appears to be largely similar to the 3M14E, which has a length of 6.2 meters (without a booster).

According to Russian statements, the 9M729 is 53 centimeters longer than the 9M728 in order to accommodate a larger, more modern guidance system. This suggests that the 9M729 is at least 6.73 meters long, though in reality it is likely somewhat longer.

In 2019, Russian state news outlet Sputnik published a graphic showing an outline of the 9M729 missile, matching Russia’s stated dimensions of a 51.3-centimeter diameter and a length of 6.73 meters. It is unclear whether Sputnik’s graphics team arrived at these measurements independently or whether the graphic was provided by official sources in an effort to corroborate Moscow’s narrative. Ultimately, this is of little importance, as the graphic offers a useful basis for the following analysis — one grounded in Russia’s own statements. I have uploaded a dimensioned graphic on my profiles on X, Bluesky, and LinkedIn, which serve as the basis for the calculations below.

Approximate dimensions of the 9M729 according to Russian specifications

Source: Fabian Hoffmann (X / @FRHoffmann1)

The funny thing is that, even when taking Russia’s self-stated numbers at face value, the missile appears highly suspect.

Assuming a length of 6.73 meters — and accounting for the foldable wings along the fuselage that pass through part of the fuel tank section, and while also assuming that roughly one quarter of the air inlet section provides additional space for fuel storage, and operating under the assumption that ten percent of the total volume is required for structure, plumbing, baffles, and unusable residuals — the total fuel tank volume of the missile is about 0.433 cubic meters. In other words, the missile can likely carry around 433 liters of fuel.

High-performance fuel equivalent to JP-10, which the Russians should have access to, has a density of 0.94 grams per cubic centimeter. This means the fuel section could hold about 407 kilograms of JP-10 equivalent fuel.

The Kalibr family is equipped with TRDD-50 turbofan engines. According to open sources, these engines have a maximum thrust of 4.4 kilo Newton, equivalent to 448.67 kilogram-force (kgf), and a thrust-specific fuel consumption of 0.7 kg/(kgf·h). This means that at full thrust, the engine burns roughly 314 kg of fuel per hour.

If the missile cruises at an average speed of 800 km/h (Mach 0.65), which likely requires approximately 60% of maximum thrust, the fuel burn is around 188 kg/h. With 407 kilograms of fuel, this yields an endurance of about 2.16 hours. Multiplying by the average cruise speed gives a maximum range of roughly 1,728 kilometers — well above the 500-kilometer INF range threshold.

The 9M729 has a maximum range of roughly 1,728 kilometers — well above the 500-kilometer INF range threshold.

If realistic engine performance figures are used, the only way the missile’s range falls below 500 kilometers would be if it carries a comically small fuel tank relative to its size. That is precisely what Russia attempted to present to observers at its 2019 press conference comparing the 9M728 and 9M729. That claim, however, is a hard one to sustain, and it comes without supporting evidence.

In short, Russia’s word should not be accepted. The analysis strongly suggests that the 9M729 has a range of well over 500 kilometers — it is almost certainly an INF non-compliant missile.

Not a “he said, she said”

The point here is not to calculate the missile’s exact range with perfect accuracy. That would be all but impossible without access to the missile itself and/or classified data. The point is that, using available information, open-source tools, and reasonable estimates and robustness tests, it is possible to show that the 9M729 very likely exceeds the INF range limits. In other words, even without access to testing records collected by the United States, which are not publicly available, there is a strong reason to believe Russia was in violation.

Even without access to testing records collected by the U.S., there is a strong reason to believe Russia was in violation of the INF treaty.

Therefore, the claim — unfortunately still made by some analysts — that we lack the tools to independently assess who was right and who was wrong regarding the 9M729 is simply incorrect, and it reflects poor research practice and judgment.

The available evidence squarely places the burden of proof on Russia. It deployed a missile system whose technical characteristics strongly suggest it was prohibited under the INF. It was Russia’s responsibility to demonstrate why the missile was permissible, but it has made no such effort — likely because it could not produce the required evidence.

In the end, if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, then it is hard to convince the world that it is, in fact, not a duck. And Russia has presented no evidence that it is not exactly what it looks like it is.

Russia’s troubled INF history

The rest of the INF story is, of course, history. There are further reasons to believe that, starting from at least the early to mid-2000s, Russia was no longer committed to the treaty and saw it not as a means to advance cooperative security, but as a tool to secure asymmetric military advantages.

The 9M723 short-range ballistic missile almost certainly has a range greater than 500 kilometers when fired on a minimum-energy trajectory — and especially when equipped with a lighter nuclear payload. Importantly, it was originally tested at a range below 500 kilometers, resulting in its classification as INF-compliant. Russia, therefore, avoided a material breach of its INF obligations, but the missile almost certainly violated the spirit of the treaty.

The 9M728 is also worth re-examining. As noted above, Russia itself acknowledges that the only difference between the two systems is an added 53 centimeters in length. Even if that entire additional volume were devoted to fuel storage, it would still be possible that the 9M728’s maximum range is well over 500 kilometers. Of course, the 9M728 was never subject to controversy, likely because Russia never tested it beyond 500 kilometers. However, based on the available data, there is reason to believe the missile was also noncompliant.

The 9M728 (R-500) missile

Photo: mil.ru

According to Russian sources, the 9M729 has been deployed since 2017 and remains in service today. Russia has never managed — nor has it made a serious effort — to dispel allegations of noncompliance.

That’s why Moscow called for a moratorium on the deployment of INF-range missiles while simultaneously fielding such systems, including the very ones that led to the treaty’s collapse. At the same time, it claimed this moratorium could serve as the basis for a follow-on agreement. Yet given Russia’s record of noncompliance, how could any state actor in Europe or North America take such an offer seriously?

Moscow called for a moratorium on the deployment of INF-range missiles while simultaneously fielding such systems, including the very ones that led to the treaty’s collapse.

Russia was never in a position to credibly propose a moratorium, and its current statements announcing it will no longer abide by it should be recognized for what they are: propaganda and a flimsy attempt to shift responsibility for the INF’s demise onto the United States and Europe, when in reality, Russia is solely to blame.

A looming missile arms race?

A popular narrative holds that the end of the INF Treaty, in the absence of a follow-on agreement, will trigger a missile arms race in Europe.

The expectation that missiles will proliferate widely across the continent in the coming years is not unfounded. In fact, it is highly probable for two main reasons — neither of which relates directly to the demise of the INF Treaty.

First, Russia’s war against Ukraine, along with recent missile engagements in the Middle East and South Asia, has demonstrated the enormous importance of missile capabilities in modern high-intensity warfare. As European NATO states prepare for a potential war with Russia — and as Russia prepares for a confrontation with NATO — both sides are likely to continue expanding their missile arsenals.

Second, Russia’s massive expansion of missile production capacity demands an equivalent response from European NATO states. In fact, Europe’s failure to act sooner to catch up with Russia’s production capacity already constitutes a major strategic oversight. At present, Russia’s annual production amounts to roughly 1,000 short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, around 2,000 land-attack cruise missiles of various types, and some 24,000 to 30,000 Geran-2 long-range one-way attack drones, along with a similar number of Gerbera decoy drones.

Russia’s Gerbera decoy drone

In contrast, European states outside Ukraine produce only an estimated 100 to 300 land-attack cruise missiles annually, with no production of conventional ballistic missiles. While some European companies manufacture long-range drones outside Ukraine, there are no confirmed European NATO customers, meaning all production is presumably destined for Ukraine.

This leaves a severe gap in missile production between Russia and European members of NATO, one that will need to be closed in the coming years. European NATO states, either independently or through multinational consortia, have begun efforts to restart missile production, but a lack of political will to invest in missile technologies at scale has significantly slowed progress.

There is a severe gap in missile production between Russia and the European members of NATO, one that will need to be closed in the coming years.

INF-range missiles — ground-based missile systems with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers — will play a role both in Europe’s missile rearmament and in Russia’s continued build-up. However, there is no indication that such systems will form the core of either side’s future missile forces.

Production of Russian ground-launched medium-range missile capabilities, including the 9M729 land-attack cruise missile and the Oreshnik ballistic missile, will likely remain far below the output of shorter-range and air-launched conventional strike weapons such as the Kh-101 air-launched cruise missile and the 9M723 short-range ballistic missile.