The Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials

The special tribunal on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, currently being planned by the Council of Europe, will ultimately be judged against the standard set by Germany and Japan following WWII. However, in practice, both countries struggled to meet the tribunals’ multiple competing demands: they were expected to hold perpetrators accountable and dismantle the legacy of aggressive war and mass repression, all while safeguarding national security amid rising international tensions. Nearly a century later, it has become clear that placing political checks on security agencies — rather than implementing a blanket purge of individual officials — proved far more effective for building effective and democratic institutions.

Armed forces and intelligence services in the dock: pondering the extent of guilt

Purge attempts vs. personnel shortages

No one is clean

Scandals surrounding questionable backgrounds

Finding the middle ground

One of the key questions at the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–1946 was the extent to which the military leadership of Nazi Germany was responsible for the crimes of the Third Reich. Two high-ranking officers were at the center of attention: Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Colonel General Alfred Jodl, who both held top positions in the High Command of the Armed Forces — Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW.

They were found guilty on multiple counts, including waging a war of aggression, carrying out mass executions, and committing crimes against civilians. In particular, the court pointed to the fact that it was their signatures on orders for deportations, reprisals against guerrillas, and the execution of Soviet officials. Both officers were sentenced to death.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

However, when it came to the military institutions themselves, the court took a different stance. Despite evidence that individual officers were complicit in criminal acts, these bodies themselves were not declared criminal organizations. The tribunal pointed to the rotating composition of the staffs, their military administrative function, and the lack of ideological cohesion. In doing so, it drew a line between the military institutions and their individual members, laying the groundwork for a restoration of West Germany's armed forces that would not involve labeling them as successors to a criminal system.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

West Germany's armed forces were not labeled as successors to a criminal system

Subsequent “minor” Nuremberg trials held by the American occupation authorities between 1947 and 1949 also sought to maintain the legal neutrality of the military hierarchy — while still doling out harsh punishment to senior officers. Military commanders were charged with committing serious crimes in occupied territories, including deportations, the forced labor of prisoners of war, the mass executions of civilians, and collaboration with the Einsatzgruppen, which were responsible for the mass extermination of Jews.

Although all of the defendants from the German military were charged with waging a war of aggression, the tribunal found them not guilty on that count, ruling that they were not part of the Third Reich's political leadership. When it came to war crimes and crimes against humanity, however, most were found guilty and received prison sentences — some of them life sentences.

The International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg also examined in detail the activities of the Third Reich’s security services: the SS (Schutzstaffel — Protection Squads), the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei — Secret State Police), the SD (Sicherheitsdienst — Security Service), and the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt — Reich Main Security Office).

The SS guarded and managed concentration camps, organized Einsatzgruppen mass executions in occupied territories, coordinated deportations, and carried out the Holocaust. The agency also oversaw the armed units known as the Waffen-SS, which took part in combat operations and punitive actions. The Gestapo conducted political surveillance, arrests, deportations, and the suppression of dissent. The SD handled intelligence both domestic and foreign, monitoring public sentiment and identifying “enemies of the Reich.” All of these structures were merged under the RSHA, a centralized coordination body that controlled the entire repressive and intelligence apparatus of Nazi Germany.

As a result of the proceedings, the International Military Tribunal declared the SS, the Gestapo, and the SD to be criminal organizations. This meant that membership in these bodies could serve as grounds for prosecution if personal involvement in crimes could be proven. There was no presumption of automatic guilt — each defendant was assessed individually. Several high-ranking officials, including RSHA chief Ernst Kaltenbrunner, were convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. They were sentenced to death.

However, tensions between the former Allies escalated rapidly after the war. With the onset of the Cold War, former Nazi intelligence officers’ expertise in countering the Soviet Union became a highly sought-after commodity, catalyzing the creation of Germany's first postwar intelligence services.

Moreover, the activities of the Abwehr — the Wehrmacht’s military intelligence service, which operated from 1920 to 1944 and was responsible for foreign intelligence and counterintelligence — were not addressed at all during the Nuremberg Trials. The Abwehr itself had been dissolved in 1944 after it lost the trust of the Nazi leadership, and its functions were transferred to SS entities. After the war, many former Abwehr officers went on to form the core of West Germany’s intelligence apparatus, particularly within the Gehlen Organization, which served as the foundation for the creation of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND).

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Former Abwehr officers formed the core of West Germany’s postwar intelligence services

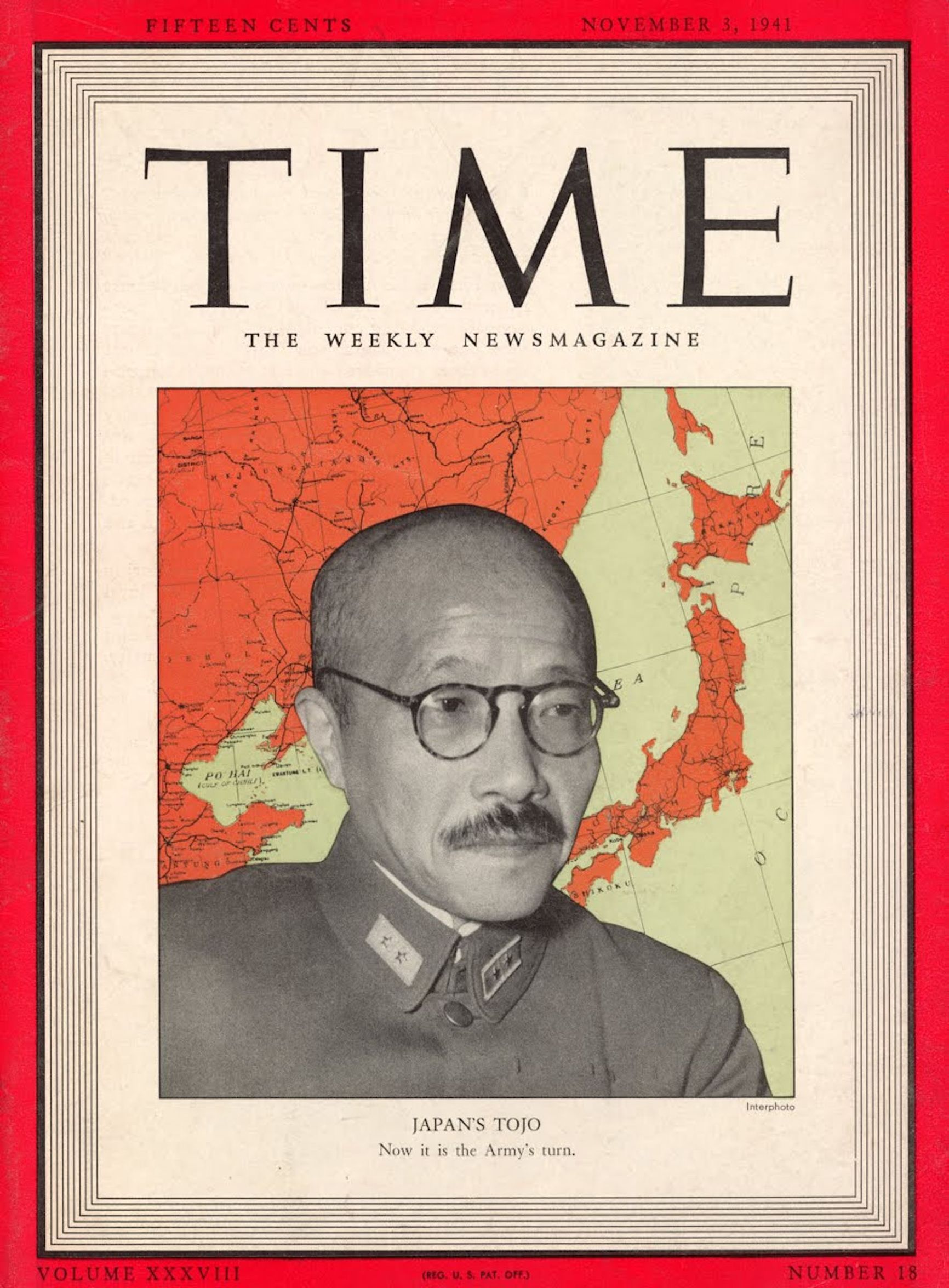

In Japan, the Allies established another international tribunal — the Tokyo Trials (1946–1948), which also prioritized the prosecution of figures from the militarist political regime. Of the 28 defendants, all but three were found guilty. Seven of them, including former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, were hanged.

However, neither Emperor Hirohito nor the Imperial Army was brought to trial. This decision, made at the insistence of the American command, was taken with the aim of avoiding the social turbulence that might follow if a key symbol of the state were dismantled.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

In addition to the main trial in Tokyo, hundreds of separate trials were held in dozens of Allied countries in order to prosecute Japanese military personnel for mass killings and mistreatment of prisoners — so-called Category B and C crimes. In total, around 5,700 individuals were held accountable, and upwards of 920 were executed. These trials played a significant role in purging the country's military — at least with regard to the senior and mid-level ranks. However, as in the case of Germany, the army as an institution remained outside the scope of institutional condemnation.

Unlike in the Nuremberg Trials, Japan's security services were not subjected to separate institutional scrutiny, and none of them were officially designated as criminal organizations. Nevertheless, during World War II, Japan maintained an extensive network of repressive and intelligence agencies, a list that included the Kempeitai (Army Military Police), Tokkeitai (Navy Military Police), Tokko (Civil Political Police), and Tokumu Kikan (Military Intelligence).

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

None of Japan’s extremely brutal security services were officially designated as criminal organizations

The Kempeitai and Tokkeitai had served as military police and counterintelligence units, maintaining discipline within the armed forces and carrying out repressive actions against civilians in occupied territories. The Tokko conducted political surveillance, suppressed opposition movements, and carried out large-scale operations against leftists and dissidents. The Tokumu Kikan coordinated intelligence and sabotage activities in China, India, Manchuria, and the USSR, including support for anti-communist and anti-colonial movements.

These services operated with extreme brutality, practicing mass repressions and torture, including against prisoners of war. They were also responsible for setting up “comfort stations” — a network of military brothels where thousands of women were used as sex slaves by Japanese soldiers.

The Tokyo Trials never convicted any of the Japanese security services as entities, effectively ignoring the issue of systemic responsibility when it came to Japan’s intelligence and police apparatus. The charges and verdicts targeted only individual leaders, primarily Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and generals responsible for war crimes.

Shortly after the war, amid escalating tensions between the United States and the USSR, the priorities of the American occupation administration in Japan sharply shifted from punishment to cooperation. As in Germany, the expertise of former Japanese security officers in combating the communist underground gained new relevance, allowing many officers of the old regime to escape accountability. Instead, they contributed to Japan’s postwar internal security organs as the Cold War escalated.

In short, the Allies’ compromise-based model allowed for the creation of new militaries in Germany and Japan — the Bundeswehr and the Self-Defense Forces, respectively — as well as new intelligence agencies that were well-equipped to contribute to the democratic world’s standoff with the Soviet Union. And the “punishment without dismantling” formula shaped both countries' national security systems for decades to come.

After the tribunals concluded in 1946, a practical challenge came to the forefront: how to dismantle the personnel base of the former militarist regimes and prevent the old elites from regaining power. Large-scale purges began in both Germany and Japan, but in practice they proved to be inconsistent and short-lived.

In Germany, the key instrument was the policy of denazification, which was carried out under the supervision of the Allied occupation authorities. It extended not only to party officials but also to the military, police, civil servants, educators, and businesspeople. In principle, every citizen who had held a significant position under the Nazi regime was required to undergo a detailed questionnaire process.

However, in the military, denazification quickly ran into practical limitations. Without a comprehensive pool of alternative personnel, a significant portion of former military officers — especially at the junior and mid-grade levels — avoided facing serious consequences. Moreover, by the early 1950s, a trend toward the “rehabilitation” of former officers had begun: in the context of the Cold War, the U.S. and the United Kingdom started encouraging West Germany’s participation in NATO’s military structures — a step that would not be possible absent the rebuilding of the country’s armed forces.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

A significant number of former Nazi military personnel — especially at the junior and mid-grade levels — escaped serious consequences

Nevertheless, in the early postwar years, genuine efforts were undertaken to prevent compromised military personnel from serving in the new army. During the formation of the Bundeswehr in 1955, a personnel screening commission — the Personalgutachterausschuss — was established. It reviewed each candidate for officer positions at the rank of colonel and above and included members of Germany’s anti-Nazi resistance in the decision process.

Out of 553 applications submitted by former senior Wehrmacht officers, 51 were rejected — mostly due to involvement in war crimes or for other compromising episodes in their biographies. Former high-ranking SS officers were subject to particularly strict screening and were barred from joining the Bundeswehr. However, by 1956, the army was permitted to accept certain former members of the Waffen-SS up to the rank of colonel.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

By 1956, the German army was already allowed to admit certain former members of the Waffen-SS

The screening of former military and political leaders in Japan was initially quite rigorous. After Tokyo’s surrender in 1945, the occupation authorities under General Douglas MacArthur launched a large-scale campaign to purge the state apparatus of figures associated with the old regime. By 1948, more than 717,000 individuals had been subjected to the process, with over 200,000 removed from their positions. Almost the entire upper echelon of the former military and administrative apparatus was eliminated from political life.

To implement this policy, special commissions were established to collect dossiers and issue rulings. In the early stage, the screening process was strict — to the extent that even moderate politicians with past ties to military institutions were removed from leadership positions.

However, by the early 1950s, this course shifted dramatically. With the Korean War raging and tensions with the USSR rising, the priorities became stability and governability rather than punishment, and a mass rehabilitation of previously purged individuals began. By 1951, many had been reinstated to influential positions in government, business, and the media.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

With the Korean War raging and tensions with the USSR rising, Japan’s priorities shifted from punishment to stability and governability

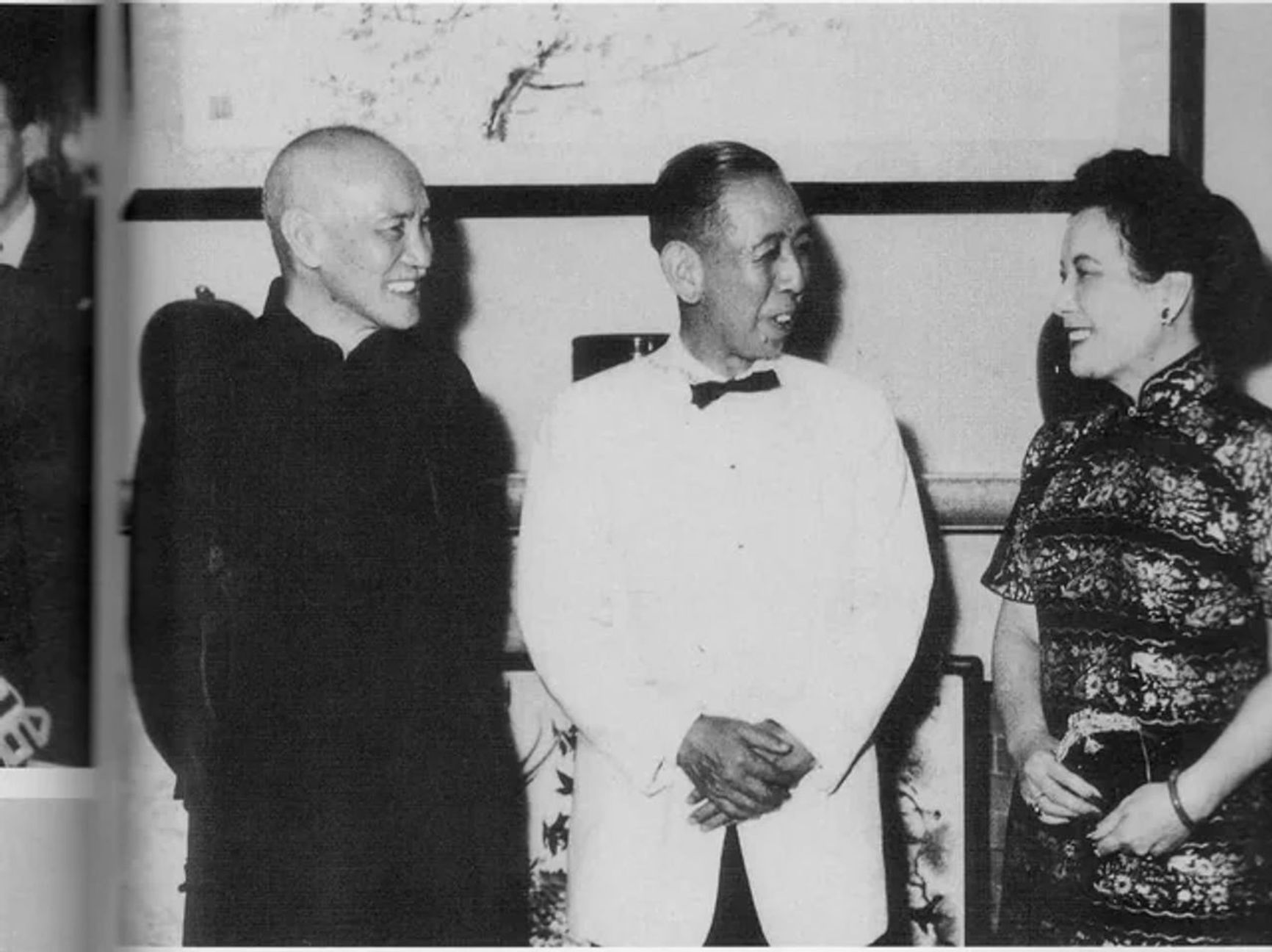

One striking example is Nobusuke Kishi, who during the war served as Minister of Commerce and Industry in General Tojo’s government and was responsible for mobilizing industry in occupied Manchuria. After the war, he had been arrested as a suspected Class A war criminal but was never brought to trial. By the 1950s, he had returned to politics and eventually became Prime Minister of Japan.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

To conclude, in both Germany and Japan, the initial drive to thoroughly purge the ranks of the military and intelligence services subsided relatively quickly — and for similar reasons: a shortage of professional personnel, shifting priorities amid the pressure of the Cold War, and a desire to restore the administrative apparatus and military capability of the occupied countries. Purges within the security sector became less a tool of true transformation and more a means of pragmatically signaling symbolic distance from the past.

By the mid-1950s, Germany and Japan were moving toward the creation of new armed forces. But how could they be controlled so as to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past?

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the new army — the Bundeswehr — began to take shape in 1955 on fundamentally new political foundations. Unlike the previous military, which was entirely subordinate to the Führer, the Bundeswehr was established as an instrument of a democratic state. Its core ideological principle was the concept of the “citizen in uniform” — a soldier loyal not to personal authority, but to the parliament and the constitution.

This idea was legally codified through the Soldier Act (Soldatengesetz) and the creation of the Military Ombudsman — a key link between the armed forces and parliament. In addition to their military specialties, new officers were educated in the fundamentals of law, ethics, and political science.

However, the new ideology was at odds with the country’s old personnel. Of the 14,900 officers admitted to the Bundeswehr by 1959, more than 12,000 (around 83%) had served in the Wehrmacht or the Reichswehr. Among the first 24,000 non-commissioned officers, nearly all were former Nazi soldiers. Creating a capable military without relying on these specialists was simply not feasible. The army even included around 300 individuals with a background in the Waffen-SS, although SS generals were not permitted to serve. As Chancellor Konrad Adenauer put it, “I don't think that NATO will accept 18-year-old generals from me.”

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Of the 14,900 officers admitted to West Germany's army by 1959, more than 12,000 had served in the Wehrmacht or the Reichswehr

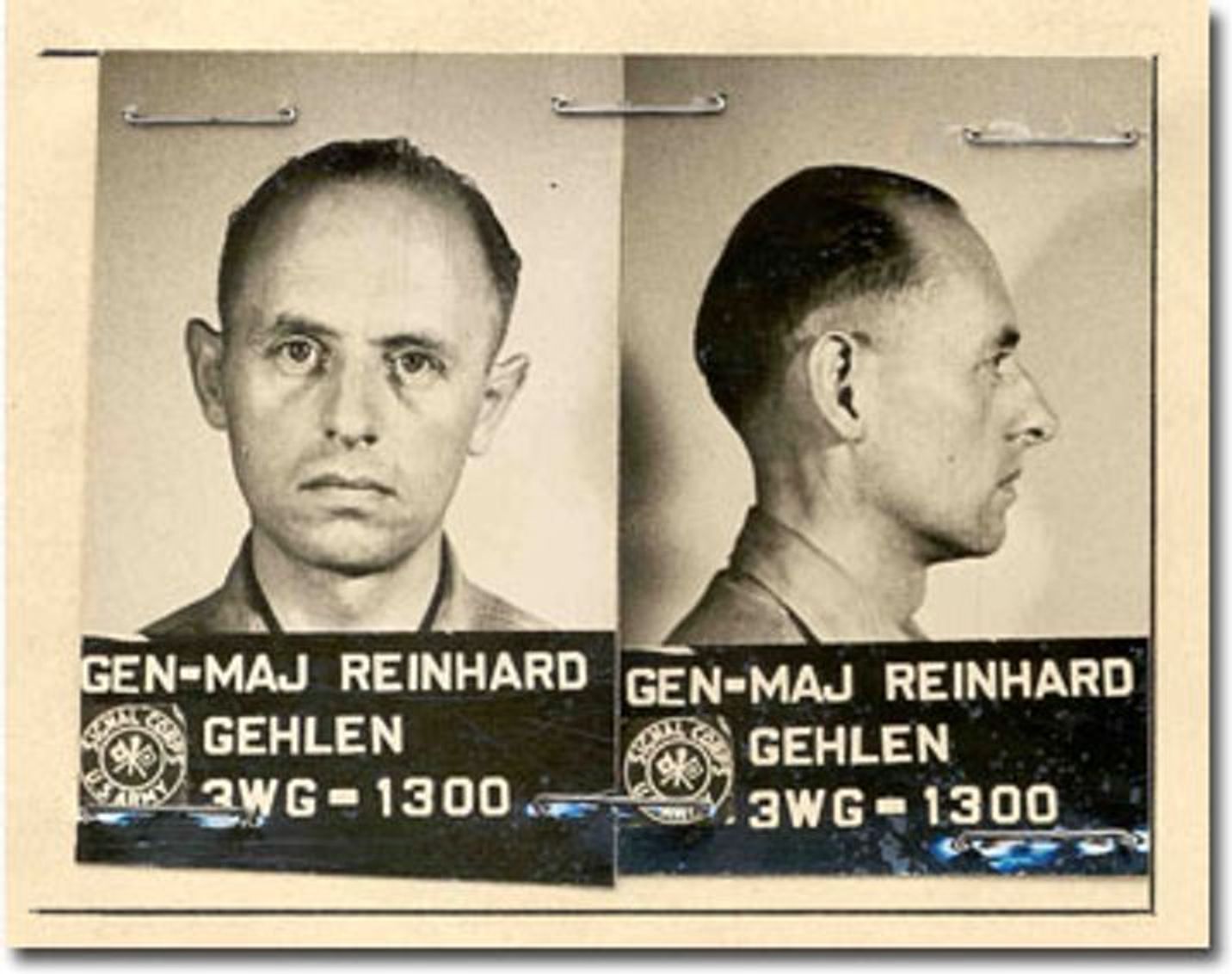

The first intelligence agency of postwar West Germany was the so-called Gehlen Organization, established in 1946 by former Wehrmacht Major General Reinhard Gehlen. During the war, he had been responsible for military intelligence operations against the USSR. After the war, with the backing of U.S. military intelligence, Gehlen began building a new structure focused on gathering information about the Soviet Union — an organization largely staffed by former members of the Abwehr military intelligence organization.

Despite receiving American funding, the new organ maintained autonomy, and coordination between Gehlen’s analytical division and Hermann Baun's operative network was weak and often marked by conflict. In 1956, the agency was transformed into West Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst, or BND).

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

The creation of counterintelligence agencies in West Germany was also a complex process. The occupation authorities insisted that the new agency must not possess police powers — a measure intended to prevent the emergence of a new repressive structure similar to the Gestapo. As a result, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV), which was founded in 1950, had a mandate to gather and analyze information on potential threats but could not make arrests or conduct searches.

A key issue in establishing the new agency was the selection of personnel. Initially, the Allies enforced strict staffing policies to prevent former Nazis from returning to government positions. However, over time — especially after control was handed over to West Germany in 1955 — former members of Nazi-era security services began entering the agency, in some cases even assuming leadership roles.

This sparked serious criticism. Hubert Schrübbers, the founder and first head of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (1955–1972), responded to the detractors bluntly: “We simply didn’t have a pool of untainted personnel at the time.”

In Japan, the restoration of the armed forces was also a gradual process. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the American occupation authorities established Japan’s National Police Reserve — a force of 75,000 personnel that soon became the foundation for the country’s future Self-Defense Forces. Despite its official status as a civilian organization, in practice the reserve functioned as a military force.

In August 1952, the corps was reorganized into the National Safety Force, and in 1954, it officially became the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). The formation of the JSDF took place under strict external oversight and with a clear effort to distance the new army from its militarist past. Leadership positions were held primarily by civilians, emphasizing the subordination of the military to democratic institutions. Former generals of the Imperial Army were barred from holding key posts, and career advancement within the forces was pursued cautiously and incrementally.

The appointment of civilian politician Keizō Hayashi as Minister of Defense was a symbolic decision that marked a clear break from Japan’s former militarist hierarchy. Emphasis was placed on a restrained, defense-oriented concept: the Self-Defense Forces were established as a means of protection within the framework of Japan’s strictly pacifist constitutional model, grounded in Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Leadership positions within Japan’s Self-Defense Forces were held primarily by civilian officials

The new security system also featured a foreign intelligence agency that was tasked with gathering information for the civilian government. Established in 1952, the appropriately named Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office — Naikaku Jōhō Chōsashitsu, commonly abbreviated as Naichō — was tasked with collecting, analyzing, and relaying information regarding international developments, military threats, and the activities of foreign states.

In the early stages, there was a proposal to make Naichō the Japanese equivalent of the CIA. However, the idea met strong domestic resistance due to fears about creating an unchecked intelligence agency reminiscent of those in prewar Japan. The compromise was to keep the agency under the direct authority of the Prime Minister, to deny it the right to conduct overseas operations, and to staff it primarily with personnel from other ministries — mainly the police force. The resulting political oversight was so robust that it impaired the agency’s independence and its capacity for active intelligence gathering.

Meanwhile, matters of domestic security were placed in the hands of another new entity — the Public Security Intelligence Agency (Kōanchōsa-chō), also established in 1952, with a mandate to detect and monitor internal threats such as espionage, extremism, and subversive activities. In its early years, the agency focused primarily on the surveillance of left-wing radical groups, including the Japanese Communist Party.

Japan's main challenge was a shortage of qualified personnel: with hardly any intelligence experts left, the authorities had to recruit former members of Japan’s disbanded prewar military and police structures. This raised concerns, but there was no alternative. Like Germany, Japan opted for a compromise, hiring experienced individuals despite their possible ties to the authoritarian past. To limit their powers, the Public Security Intelligence Agency (PSIA) was placed under strict legal constraints from the outset: any investigation required approval from an independent commission, and agency officers had no authority to make arrests.

In both Germany and Japan, the creation of security agencies was the result of numerous compromises. A complete purge of individuals with questionable pasts was never accomplished, but a combination of thorough vetting and special restrictions succeeded in compelling security personnel to work within the constraints of new democratic values. Vetting mechanisms and checks remained in place.

Despite all the vetting and reform, neither country was immune to scandals and concerning the past misdeeds of their military personnel. Such controversies were especially pronounced in West Germany during the 1960s.

One of the most high-profile cases was that of General Adolf Heusinger, a former Wehrmacht lieutenant general who held a key position in the army's operational staff, planning the war on the Eastern Front. In postwar Germany, he became the first Inspector General of the Bundeswehr and later chaired the NATO Military Committee. The Soviet Union publicly demanded his extradition as a war criminal, accusing him of punitive operations on the territory of Belarus.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Another noteworthy case involved General Hans Speidel, who during the war served as Chief of Staff of German forces in France and was suspected of involvement in reprisals against hostages and the deportation of Jews. Despite these accusations, he had a successful career in the Bundeswehr, eventually commanding NATO’s Allied Land Forces Central Europe. However, in 1963, he was forced to retire, reportedly at the insistence of French President Charles de Gaulle. For Paris, after all, Speidel embodied the memory of the Nazi occupation.

The intelligence services of West Germany — especially its domestic security agency, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution — also lived through its share of scandals involving former Nazis. This should not have come as a surprise, given that in the 1950s one-third of its personnel consisted of former members of the NSDAP.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

In the 1950s, one-third of the official personnel of West Germany's new counterintelligence agency in the 1950s were former members of the NSDAP

For example, Erich Wenger, a former Gestapo officer and SS member who was investigated after the war for the execution of prisoners of war, was considered a key figure in the operational work of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Otto Gunia, who headed the security department in West Germany’s counterintelligence agency, previously served in the RSHA (Reich Main Security Office of the Third Reich) and was involved in developing racial theory. Richard Gerken, another counterintelligence chief, was a member of the NSDAP and an SS candidate who had conducted sabotage and subversive activities.

The former director of the Wehrmacht Secret Police, Karl Eschweiler, headed the department for state secrets protection in West Germany’s counterintelligence agency. Even the agency’s president from 1955 to 1972, Hubert Schrübbers, was a member of the SA and SS before 1945 and took part in the prosecution of individuals accused on racial and political grounds.

In 1963, Der Spiegel revealed 25 counterintelligence employees with pasts in the Gestapo, SS, or the Security Service, and the cases of 16 of them were considered particularly egregious. Only under public pressure did the agency begin a gradual purge, which was completed only in 1975 with the resignation of Günther Nollau, the head of the service, who had been a member of the NSDAP from 1942 to 1945 and had fought in the war on the Eastern Front.

Scandals of a similar scale did not arise in Japan — in part due to the greater secrecy of the military structures, but also simply because of the absence of such intense public debate. Unlike Germany, Japan saw almost no societal discussion about the acceptability of staffing decisions. In practice, the rehabilitation of former elites took place behind the scenes of bureaucratic procedures and under the cover of silent consent. Instead of having an open discussion about its army's role in the war, Japanese society chose a strategy of silence and forgetting.

The experience of Germany and Japan shows that cleansing security forces after the fall of authoritarian regimes requires political will. After their most egregious war criminals were punished by the tribunals, both countries faced the practical challenge of building new security structures amid a severe personnel shortage and growing external threats.

As a result, the initial drive to conduct large-scale purges gradually gave way to selective screening and limited rehabilitation. Commissions, background checks, and ideological restrictions helped remove the most odious individuals, but neither country could fully sever ties with its respective past. Still, reforms limiting the power and capabilities of the German and Japanese militaries made it all but impossible for either state to embark on another path of imperial conquest.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari