China faces mounting challenges, the result of a real estate bubble, a stock market crisis, and a growing debt burden. These issues loom large amidst dwindling investments, a factor that is itself largely the result of strained relations between Beijing and the West. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggests that China stands at a crossroads: it can either continue on its current path of impoverishing autonomy, or it can change direction by taking the more internationally focused route to development that Beijing seemed to be following before the pandemic.The IMF insists that without reforms, a return to previous levels of growth is unattainable. The decision China makes will significantly impact the global economy.

Content

China's problems: can they be resolved?

Relations with the West and Taiwan

What the IMF recommends

What to expect: four scenarios

“China stands at a crossroads — it must decide whether to rely on policies of the past or reinvent itself for a new era of quality growth,” remarked Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), this past March at the China Development Forum in Beijing. She believes that through a “package of market reforms,” China could add 20%, or $3.5 trillion, to its economy over the next fifteen years.

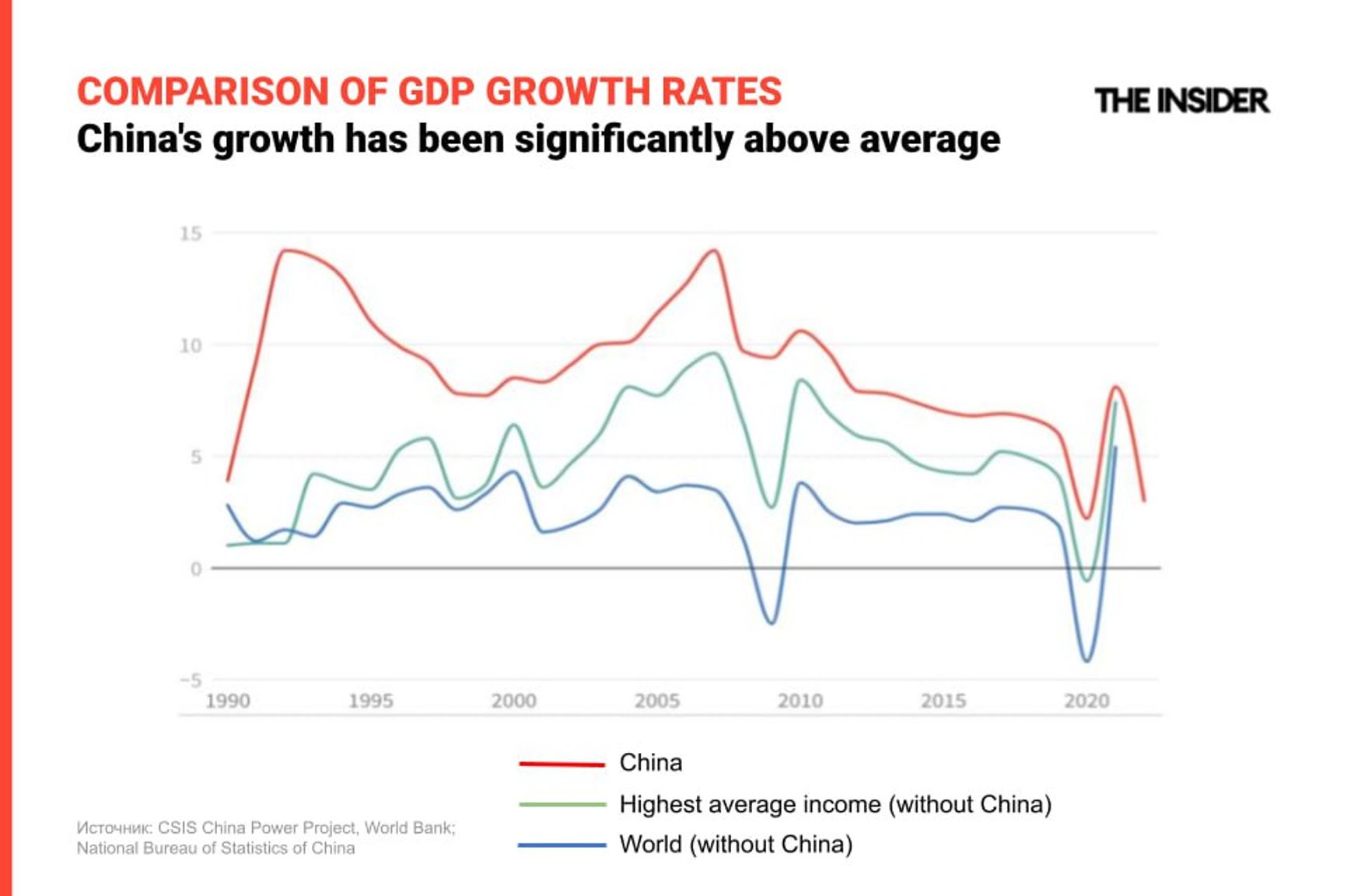

Currently, China appears to be emerging from the shadow of the coronavirus crisis: GDP growth in 2023 surpassed expectations — 5.2% rather than the predicted 5.0% — but the figure is likely to remain far below the double digit annual results often produced during the country’s meteoric rise from poverty to modernity over the past few decades. Complicating matters in the world's second-largest economy are deflation, an aging population, and challenges in its vital real estate sector.

Even Chinese President Xi Jinping, typically reticent about acknowledging problems, mentioned obstacles to economic growth this year, including unemployment, a rise in poverty, and issues related to specific sectors. Given China’s pivotal role in driving the global economy in recent decades, both by mitigating the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 and the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, Beijing’s level of success in coping with these challenges will have global ramifications.

hukou

The passport system in China, which ties residents to a specific region and rigidly categorizes them as rural or urban, serves as a tool to control internal migration and, particularly, urbanization. However, this system impedes the movement of the workforce between regions.

China is expected to drive 35% of global growth in 2023–2024, but this share is projected to decrease to 30% in 2025, according to calculations by the World Bank. The sluggish recovery of its demand will hinder global trade, including in commodities, and constrain the growth of global GDP. IMF experts caution that both the region as a whole and China specifically are facing significant economic headwinds.

China's problems: can they be resolved?

China finds itself in a complex situation as multiple systemic contradictions compete for attention simultaneously. Chief among these is its export-oriented economy, which relies on interdependence with trading partners at the same time the authoritarian regime in Beijing inclines towards protectionism and promotion of the domestic market. There are several potential flashpoints.

- Real estate bubble

The real estate sector, along with construction, has been one of China's fastest-growing industries over the past two decades. At its peak, China was constructing twice as much new square footage as the United States each year. By 2006, a quarter of all domestic investments went into real estate, and by 2022, the sector accounted for a quarter of China's entire GDP. The development was even domestically driven, with the construction industry relying on only a 25% share of imported materials. This self-sufficiency and focus on internal demand ensured developers stable government support in the form of subsidies and cheap loans. However, the downside was the blurring of lines between the public sector and private real estate.

Concerns about a bubble emerged in the 2010s as rising demand and steadily increasing prices in certain areas paradoxically combined with a surplus of vacant properties in others. Overall, property prices soared by 350% over 15 years by 2021, and yet much of the new construction remained empty.

The strict lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent economic slowdown significantly exacerbated the situation. Meanwhile, the government decided to tighten regulations in an attempt to cool the market. In 2020, it introduced the “three red lines,” requiring developers to reduce their debt-to-asset ratio, debt-to-equity ratio, and short-term debt ratio. This led to a slowdown in lending growth, reduced economic activity among developers, and decreased profits. Compared to the typical growth rate of around 20%, the real estate market contracted by 17% in investments, 20% in sales, and 35% in new construction projects in 2023.

The most significant shock came with the dissolution of the Hong Kong division of China's largest developer, the China Evergrande Group. While other companies within the group pledge to “maintain uninterrupted operations,” Evergrande has already set a global record among developers for its accumulated liabilities, totaling $300 billion.

Another major player, Zhongzhi Enterprise Group, one of China's largest investment firms, has also filed for bankruptcy and liquidation. Despite once managing a portfolio worth $140 billion, the company's assets now amount to only half of its debts.

Beijing is now devising a 20-year plan to restructure debts in the real estate market and dispose of bad loans. However, whether this will offer short-term relief remains uncertain.

- Stock market sell-off

Amidst a prolonged housing market crisis and persistent deflationary pressures in the economy, holders of Chinese stocks have been offloading them for nearly the entire past year. By late January, the key CSI 300 index had plummeted to five-year lows before experiencing a slight rebound. Over the past three years, it has shed over $6 trillion in value.

In response, the government is gearing up to inject approximately $280 billion into the market through a stock purchase stabilization fund. These funds are expected to be sourced from offshore accounts of state-owned enterprises. Additionally, they have earmarked $42 billion from local funds to invest in stocks through entities like China Securities Finance Corp. or Central Huijin Investment Ltd., as reported by Bloomberg sources.

However, despite these measures, major international and retail investors remain skeptical about the market's prospects, doubting whether these injections will be sufficient to spur a sustainable rebound.

Stocks represent a significant portion of household wealth, alongside real estate. Hence, this systemic risk poses a threat to financial stability.

- Bad debts

China is eager to maintain vigorous economic activity and thus actively encourages borrowing. However, if corporations or municipalities find themselves unable to repay these loans, the state intervenes, either by forgiving debts or offering subsidies. Complicating matters, banks are hesitant to disclose credit issues prematurely, fearing market or governmental repercussions, allowing bad debts to become worse still.

Private debt levels in China have steadily climbed over the past decade, placing a growing burden on banks. In 2023, a record 8.5 million borrowers defaulted on mortgage or entrepreneurial loans, landing them on blacklists.

While China's external debt stands at a significant $2.38 trillion, that figure is gradually decreasing. However, the more concerning aspect lies in the hidden debts of cities and provinces, estimated to be between $7–11 trillion. This vulnerability makes the system highly susceptible to crises, offering the potential for a domino effect in the event of a shock to the system. Additionally, the debt burden of private corporations is on the rise, with an increasing number operating at a loss and earning the moniker of “zombie companies.”

These issues stem from one very particular aspect of China's centralized economy — soft budget constraints. Other systemic problems often arise from the intricacies of state involvement in the Chinese economy. Analysts believe that Beijing's direct control over the banking sector repels both foreign investors and local major capital, thereby depriving it of an external input that might otherwise have aided economic growth and helped to alleviate debt issues.

However, China's sporadic attempts to restructure its economy in response to crises, including sudden economic liberalization campaigns, have often yielded results opposite to what was intended. While private entities could potentially benefit from such liberalization, they are wary of the accompanying unpredictability.

Relations with the West and Taiwan

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has not only disrupted the global economy, but has also exacerbated tensions between China and the West. China's reluctance to openly denounce Russia and support Ukraine has strained its already delicate relationships with the United States and Europe.

Nevertheless, China remains keen on bolstering its economic ties with the West, particularly with European nations. This intention is evident from the diplomatic visits of Foreign Minister Wang Yi to Europe, the warm receptions of European delegations in China, and President Xi Jinping's public calls for foreign investment in China. However, Beijing has yet to make a definitive choice between Western prosperity and Russian autocracy, and this indecision only further harms the Chinese economy’s prospects for recovery.

The issue of Taiwan further complicates Beijing's relations with the West. Tensions escalated following President Xi Jinping's New Year statement asserting the “inevitability” of the island’s reunification with the mainland. However, Xi has been openly discussing this topic since at least 2014 — and no invasion has yet materialized. Serious deliberations intensified in 2016 with the election of Tsai Ing-wen as Taiwan's president. Unlike the Kuomintang party, which has dominated politics in Taipei for decades, Tsai's faction leans towards supporting Taiwan's outright independence and is less receptive to the 1992 consensus on a “one China” approach. This stance irks Xi, who often resorts to indirect threats, primarily through military exercises near the island, in an attempt to influence his de facto independent neighbor's behavior.

Such military aggression is causing concern on the part of both the government of the Republic of China and in Western countries. The negative response from Beijing to Tsai's re-election in 2020 and the election of her party colleague, William Lai, in the January elections this year has led to further military “maneuvers.”

Following elections on the island, it has become almost routine to witness escalations of the Taiwan issue, along with overseas trips by Taiwanese politicians and visits by foreign diplomats. In response to each escalation by China, Western countries, particularly the United States, offer assurances of support for Taiwan.

Many military experts in the U.S. believe that their country is fully capable of successfully intervening in a potential conflict, and only time will tell if Beijing is serious about blockading or invading the economically prosperous, democratically run island. This situation has created extreme tension, as both Washington and Beijing are acutely aware of the likely consequences of kinetic confrontation. They are thus striving to maintain dialogue. For instance, representatives from both countries met in Bangkok earlier this year.

Again, a full-scale invasion is not inevitable, and some experts suggest that Beijing may reconsider its hardline stance towards Taiwan and seek to balance coercion with incentives. In the unlikely event of an all-out war, the Chinese economy — just like the global economy — would face a widespread recession, prolonged inflation, and the potential for a series of national defaults.

However, even without further escalation, the current tensions between Beijing and Taipei significantly impact China's prospects for increasing material prosperity. Besides hindering China's efforts to forge closer ties with Western partners, the conflict also obstructs economic cooperation across the Taiwan Strait. For example, investments in China from Taiwan have seen a significant decline in recent years, dropping by 34% in 2023.

What the IMF recommends

To maintain China's pivotal role in the global economy, the IMF emphasizes the need for decisive actions in the real estate sector, allowing market forces to rectify the growing imbalances. Their suggestions include implementing buyer insurance against the risk of incomplete construction, introducing a nationwide property tax, and incentivizing savings. Furthermore, fiscal reforms are essential to address the gap between the income and spending obligations of local authorities.

A significant shift should focus on bolstering domestic consumption. This would require taking steps to enhance the purchasing power of the populace, particularly retirees, and would thus demand reforms to the pension system. Currently, urban residents predominantly benefit from pensions, while their rural counterparts receive minimal support. Additionally, there is a pressing need to relax the rigid urban-rural divide imposed by the household registration system, known as hukou.

Overall, a gradual transition towards a service-oriented economy is necessary, alongside a departure from reliance on low-skilled labor, as recommended by the IMF. The existing level of economic development and productivity supports such a transition.

As sinologist Mikhail Korostikov told The Insider, implementing the IMF's suggestions may not align with Beijing's political agenda, which remains moderately anti-Western: “The proposals set forth by the IMF for China — investments in education, healthcare, social services, addressing real estate market challenges, and stimulating domestic demand — ironically echo the sentiments expressed by Chinese officials themselves. Thus, the issue lies not in China's actions being incorrect, but rather in the gap between rhetoric and action.”

hukou

The passport system in China, which ties residents to a specific region and rigidly categorizes them as rural or urban, serves as a tool to control internal migration and, particularly, urbanization. However, this system impedes the movement of the workforce between regions.

The issue lies not in China's actions being incorrect, but rather in the gap between rhetoric and action

Still, the process of putting into place some of these reforms — expanding domestic consumption, reducing reliance on export-oriented sectors — had been underway for the past decade, the expert explains. However, they were halted due to the pandemic and have not resumed since. “The coronavirus pandemic showed that in the face of serious disruptions, the country quickly loses manageability, and China's attractiveness rapidly diminishes. The Chinese leadership dislikes surprises the most. During the pandemic, they handled them exceptionally poorly. Therefore, the accelerated implementation of the reforms proposed by the IMF is likely perceived by them as a precursor to even greater instability and chaos.”

Even the real estate market bubble is less alarming. “As the late former Premier Li Keqiang once said, in China, bubbles are made of iron. This means they can be controlled until the last moment. A global catastrophe must occur for China to allow this real estate bubble to burst and lead to a crisis,” Korostikov added.

What to expect: four scenarios

The further unfolding of events can be hypothetically divided into several scenarios.

In the first scenario, which is conservative yet relatively optimistic, developments unfold without any dramatic collapses or unforeseen positive shifts (i.e., there is no cessation of hostilities between Russia and Ukraine, no substantial thaw in U.S.-China relations, and no rapid rebound in the real estate sector). IMF analysts highlight the relative likelihood of such a scenario in their projections.

In this case, China will continue to grapple with its core issues. The real estate bubble will gradually deflate, leading to price declines and a high likelihood of non-repayment of construction loans. However, instead of a sudden crash, the market would be expected to stabilize gradually. External challenges and strains in international relations would persist, and the authoritarian tendencies of the Xi regime towards tighter control over both public policy and the national economy would remain a significant check on the market. In such a scenario, China's economic growth would decelerate but remain steady, with a projected 4.6% GDP growth in 2024, while the global economy would maintain a stable growth rate of around 3%.

The second scenario presents a pessimistic outlook when compared with the IMF's baseline projections. In this case, China will continue grappling with familiar challenges, none of which are anticipated to trigger acute crashes or collapses. However, China would struggle to offset these challenges, instead continuing to bolster its investments in low-cost, low-return manufacturing while the transition towards services and more lucrative economic projects unfolds at a sluggish pace. If this happens, analysts anticipate China's annual growth to hover around 2% until approximately 2029.

The third scenario involves the real estate bubble finally bursting, precipitating a financial crisis. In this case, the high levels of accumulated debt will be impossible to manage due to the complete collapse of the sector, resulting in a sharp slowdown in capital flows and a drop in internal investments that will reverberate through other industries. This scenario forecasts the peak of the crisis to occur sometime around 2027, when China's growth essentially stagnates. Such an event could potentially trigger a global recession or, at the very least, a significant slowdown in global GDP growth.

The fourth scenario is intertwined with geopolitical risks, including deteriorating relations with the West and an escalation in the trade war with the U.S. Heightened tariffs and reduced trade volumes with major partners would severely impact China's economy, although these would still be less likely to lead to a financial crisis as severe as the one outlined in the real estate market crash scenario. This scenario could start to unfold around 2025, as it largely hinges on the outcome of this November’s presidential elections in the U.S. If Donald Trump again becomes president and again pursues a confrontational economic relationship with Beijing, China’s GDP growth rates would likely hover around 1.5%.

While the more catastrophic scenarios are likely to be avoided, it is still premature to expect China to return to its pre-crisis growth levels. While the IMF notes that Beijing retains the potential to reverse this trend, it remains equally plausible that Xi's leadership will lead the country into a stagnation trap similar to the experience of Japan. This would offer India, which has outpaced Chinese growth rates for several years while also surpassing China in population size, the chance to emerge as a regional leader.

hukou

The passport system in China, which ties residents to a specific region and rigidly categorizes them as rural or urban, serves as a tool to control internal migration and, particularly, urbanization. However, this system impedes the movement of the workforce between regions.